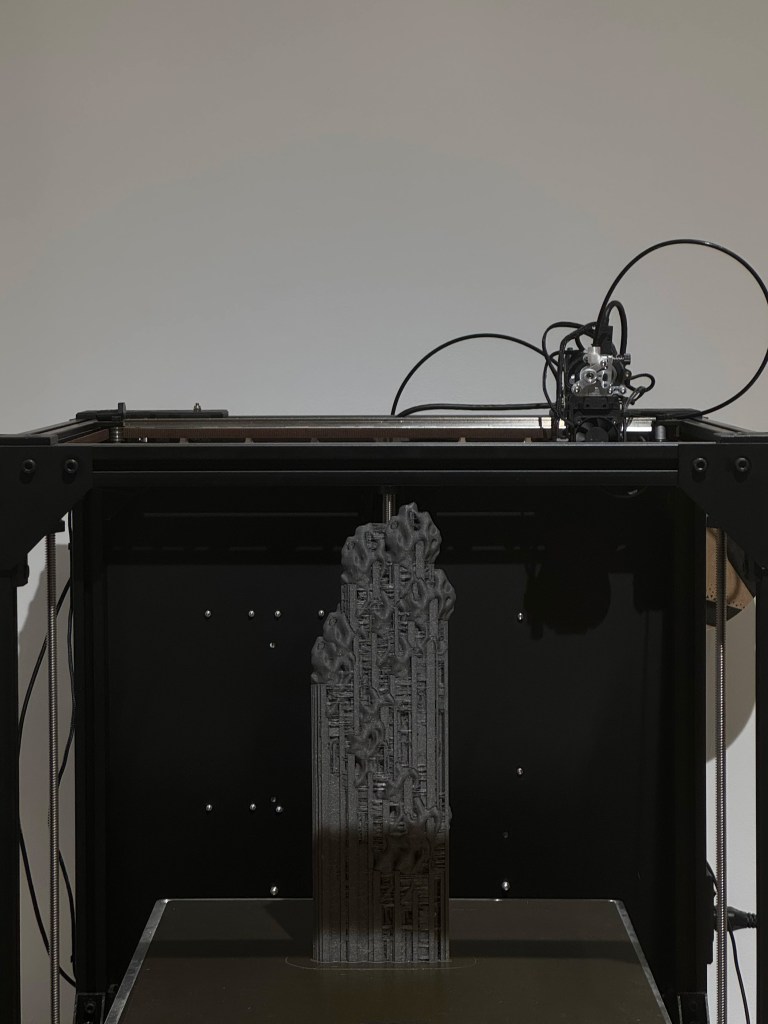

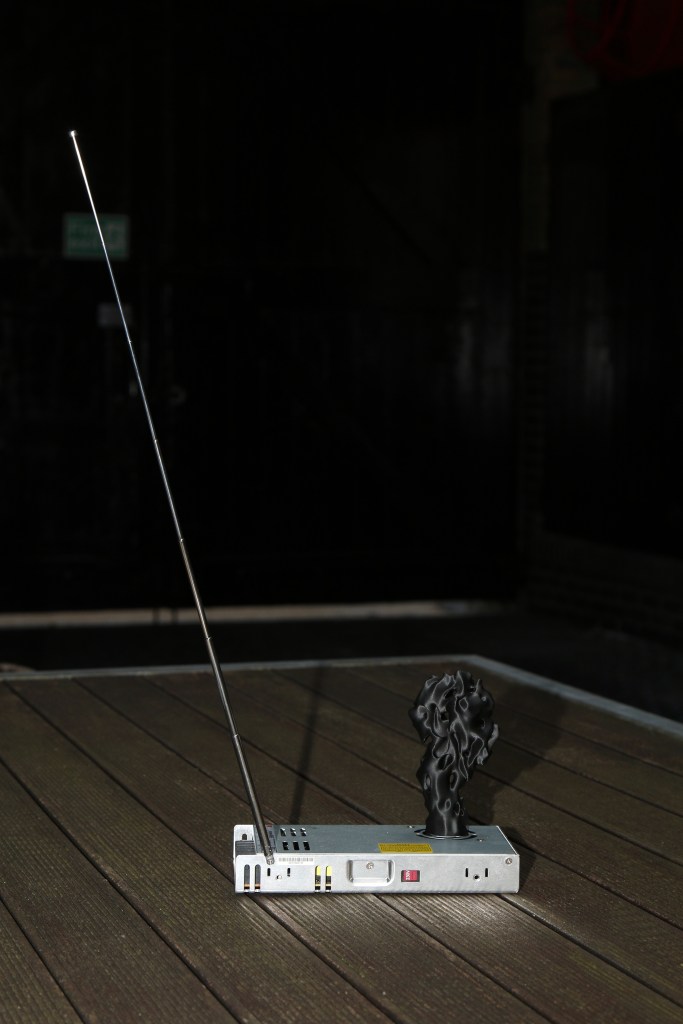

↑ Untitled; Size: 240*120*350 /mm; Material: 3d printed-PLA, power supply, Aerial Antenna

Hao Huang is a contemporary artist known for his innovative fusion of traditional Chinese aesthetics with digital mediums. His acclaimed series, Fetishism Landscape, reinterprets the classic Taihu stones, embedding them with commercial and consumerist symbols to challenge perceptions of value and authenticity in a rapidly evolving cultural landscape. Huang’s work invites viewers to explore the intersection of heritage and modernity, prompting a deeper reflection on materialism and symbolism in today’s society. This interview offers insight into his creative inspirations, processes, and the themes that drive his artistic vision.

Hao Huang website

In your series Fetishism Landscape, you juxtapose traditional Chinese Taihu stones with symbols of consumerism. What led you to use these particular cultural and commercial references, and what deeper social commentary are you aiming for?

I found myself drawn to Taihu stones through my first job after graduating from college.I was hired by a collector of these stones, and my role was to transform them into trendy cultural products. In a way, my creations were simply part of the job. Traditionally, Taihu stones symbolise the Daoist concept of “oneness between humans and nature” in ancient Chinese philosophy. Engaging with these stones is not merely an aesthetic experience but also a spiritual one, allowing individuals to project their inner emotions onto the stone’s unique shapes—a very enriching relationship.

Ironically, my work involved stripping away this cultural significance to turn the stones into consumer products. I redesigned them into functional objects with flocked surfaces, metallic finishes, glossy textures, and appealing colours, making the stones look like fashionable items ready to be consumed. I wasn’t intentionally setting out to juxtapose these symbols to create an absurd scene; rather, I was reflecting the reality of today’s social landscape. What I’m trying to convey is the extent to which consumerism has reshaped Chinese society and how cultural symbols are alienated in the process. It forces the viewer to confront the disconnect between surface appearances and deeper truths, a gap that exists on both personal and societal levels.

The blending of virtual and physical elements plays a key role in your work. How do you see the evolving relationship between digital art and traditional craftsmanship?

Digital art aligns well with the needs of my creative concepts, allowing me greater freedom to manipulate visual elements. With the precision of 3D printing, I can reproduce these designs with a level of detail that traditional craftsmanship could never achieve. However, this approach also requires constant awareness.

I need to consider how to balance the creative relationship between humans and machines, and how to preserve the uniqueness of craftsmanship and the human spirit in the digital age. In my view, a good piece of work is a journey—it should look forward to explore new materials and techniques, while also looking back to engage in dialogue and reflection with traditional craftsmanship.

How has your cultural background influenced your exploration of materialism and symbolism in contemporary art?

When it comes to discussing my cultural background, I take pride in it, but only in the traditional aspects of Chinese culture. The rapid modernisation and wave of consumerism have left us in a society with a cultural disconnect. As I mentioned in my first response, living in such an absurd reality means there’s no need to deliberately search for contradictions—they are already present. Simply reflecting the present moment becomes the best form of introspection.

This reminds me of photographer LI Zhengde’s work——The New Chinese. where he abandons flashy techniques to authentically document the faces of people from different social classes in Shenzhen over a decade. His photos capture the many postures of Chinese individuals trying to imitate Western consumer culture during a time of social transformation and Western cultural influence.

What challenges or discoveries have shaped your approach to integrating virtual sculptures into cultural conversations about value and utility?

To be honest, I really enjoy this process because the concept itself is interesting. The idea of deliberately designing objects where form takes precedence over function allows me to fully indulge in the pleasure of visual design. However, digital art is not my ideal form of expression—I want to materialise these sculptures, which presents certain challenges. You inevitably have to make compromises regarding scale, material, and fabrication, so finding a good balance is crucial.

Moreover, I’m not entirely satisfied with creating individual sculptures; I want them to come together to form a parallel world. I see this as a challenging goal, and it’s also something that excites me.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

Although it’s a big question, I actually enjoy answering it. Art requires maintaining a sense of curiosity; you need to perceive the world like a highly sensitive sensor. Here, I’d like to share Neri Oxman’s interdisciplinary theory. She suggests that knowledge produced by science is utilised by engineers, the practical applications developed by engineers are used by designers, and designers alter behavior, which is then perceived by artists. Art generates new perspectives on the world, providing people with fresh insights about how the world works, and in turn, inspires new scientific exploration. I strongly agree with this viewpoint, and it aligns with my specific goals as well.

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’24