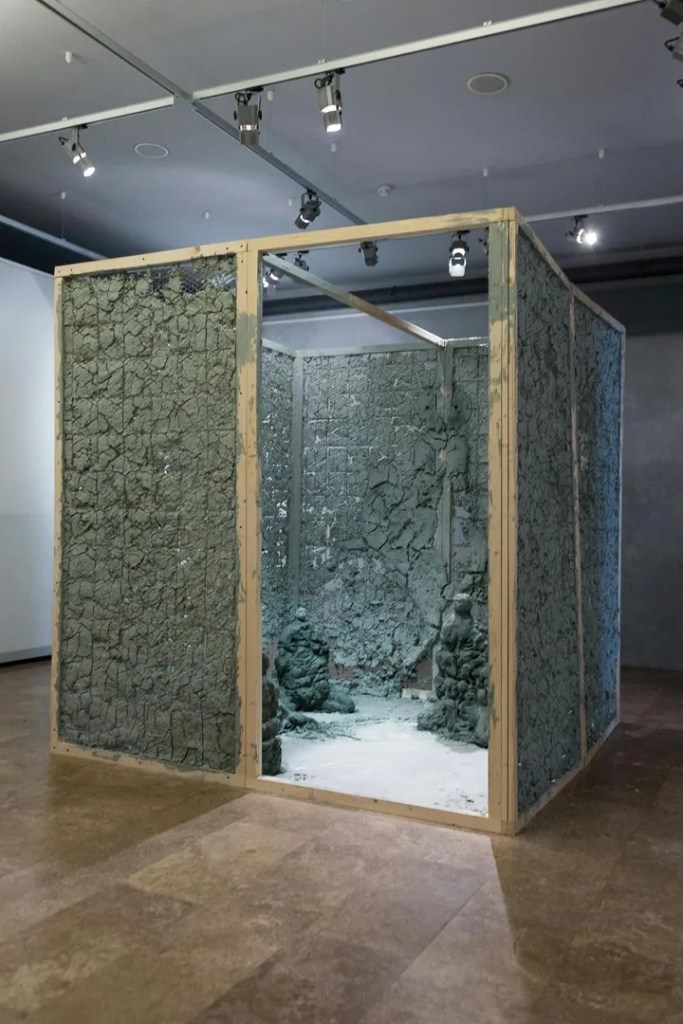

↑ Nikita Seleznev studio in New York, USA, Photos courtesy of Lima Lipa @bulochka_s_pereulochka_

Nikita Seleznev is a multidisciplinary artist whose work navigates the intersection of personal identity, societal structures, and the human experience. With a background in sculpture and a practice that spans installations, performances, and sound art, Nikita’s projects challenge perceptions and invite audiences into deeply reflective spaces. From the thought-provoking performative work My Space to the metaphor-rich Shaving of the Christ, their art addresses complex cultural and social narratives with a bold and innovative approach. In this interview, we delve into Nikita’s inspirations, creative processes, and the stories behind their compelling works.

Your project “My Space” involved a three-week performative work where you created objects in a virtual cell, reflecting cultural and social layers connected to your generation. Can you share more about the inspiration behind this project and how it influenced your artistic development?

I created this work right after graduating from the St. Petersburg Academy of Art and Design. It’s one of those traditional academies where senior professors revere Picasso and Braque, discuss Hellenistic traditions, and emphasize the classical proportions of architecture. Students draw and sculpt from life every day, trying to find ways to apply these skills in the modern world. The longer I stayed in this utopian circus, the more I thought about what I wanted to do as an artist.

The opportunity to present my reflections came shortly after completing my studies. At the Museum of Urban Sculpture in St. Petersburg, I constructed a tiny studio made of clay applied to a wooden frame. Over a month, I used my skills as a craftsman to create a whimsical, individual world. In this space, Kurt Cobain’s quotes covered the floors and walls, the feet of workers and soldiers—figures I often saw in Soviet books—trampled pots and vases, and strange creatures sat here and there, observing everything.

It was a work by someone just beginning their artistic journey—slightly confused but passionately searching. These same explorations led me to work with stop-motion animation and sound, — media that helped me shape my artistic language.

In “Shaving of the Christ,” you used a metaphorical reference to Jesus Christ to reflect on how individual human life is devalued in authoritarian regimes. What motivated you to explore this theme, and what message do you hope to convey through this work?

The project is a stifled cry, a gasp, a sob—an emotional response in a situation where one feels powerless. It is a simple yet emotional work about the value of every life and the disgusting humiliation of human dignity.

Your project “Phonatory Bands” added sound to emphasize the mysteriousness of a building during the Prospect Art Festival, allowing the audience to hear disturbing and mysterious sounds of sea creatures. How do you approach incorporating sound into your installations, and what role does it play in enhancing the viewer’s experience?

I started exploring sound because I didn’t know how to work with sculpture anymore. After studying it for so long, the weight of knowledge began to press down on me. Everything seemed already done, not mine. But with sound it was different, I knew nothing about it , and I could freely experiment.

I invited my friend, the incredibly talented composer Marina Karpova, to collaborate. She proposed an unexpected format of interaction. For several months, she mentored me in creating music, showing me the hidden structures of musical compositions, technical techniques, and, most importantly, a love and passion for this craft.

After our sessions, I created several compositions, earning Marina’s comment: “You make music like a sculptor.” To me, it was an ideal responce.

I was very happy when the Art Prospect Festival gave me the chance to give a voice to one of St. Petersburg’s most mysterious buildings—a former church transformed by Soviet constructivists into a community center. I chose the strangest of my compositions and gave the building its missing voice.

Having studied sculpture at the St. Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design and participated in various international exhibitions and residencies, how have these experiences shaped your artistic practice, and what perspectives have you gained from working in different cultural environments?

I have always been drawn to the most niche and overlooked heroes and areas of art, which is why I turned to stop-motion animation in the first place. Its strange and enigmatic world inspires me. All my characters are peculiar outsiders placed in contexts that reflect our social realities. My goal is to use them to comment on the changes I observe while conveying the warmth and respect I feel for these characters.

The more international my experiences and practice have become, the more focused my work has grown. I love New York for its diversity of art and its energy. Here, I have come to fully understand that there is no “right answer” in art—only your individual perspective and the opportunity to say something that matters most to you.

Suburbia, 2020, Installation. Sound speaker, sculpture (concrete, metal, found object, styrofoam, textile), c-print, screen.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

I believe that, since the late 19th century, the primary role of the artist has been to be the first to grasp unspoken changes in the social environment and to find a pre-verbal, emotional form to express them.

In the modern technological context, where the creation and exchange of signs have reached unprecedented speeds, it seems that the role of art has shifted toward curation and focusing attention. Endless news feeds, memes, images, and messages capture even the slightest anxieties and changes. Amid this torrent, the role of art may be to slow down, focus, and condense emotions that are otherwise lost in the stream.

Photos courtesy of Lima Lipa @bulochka_s_pereulochka_

Nikita Seleznev website

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Premier Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’24