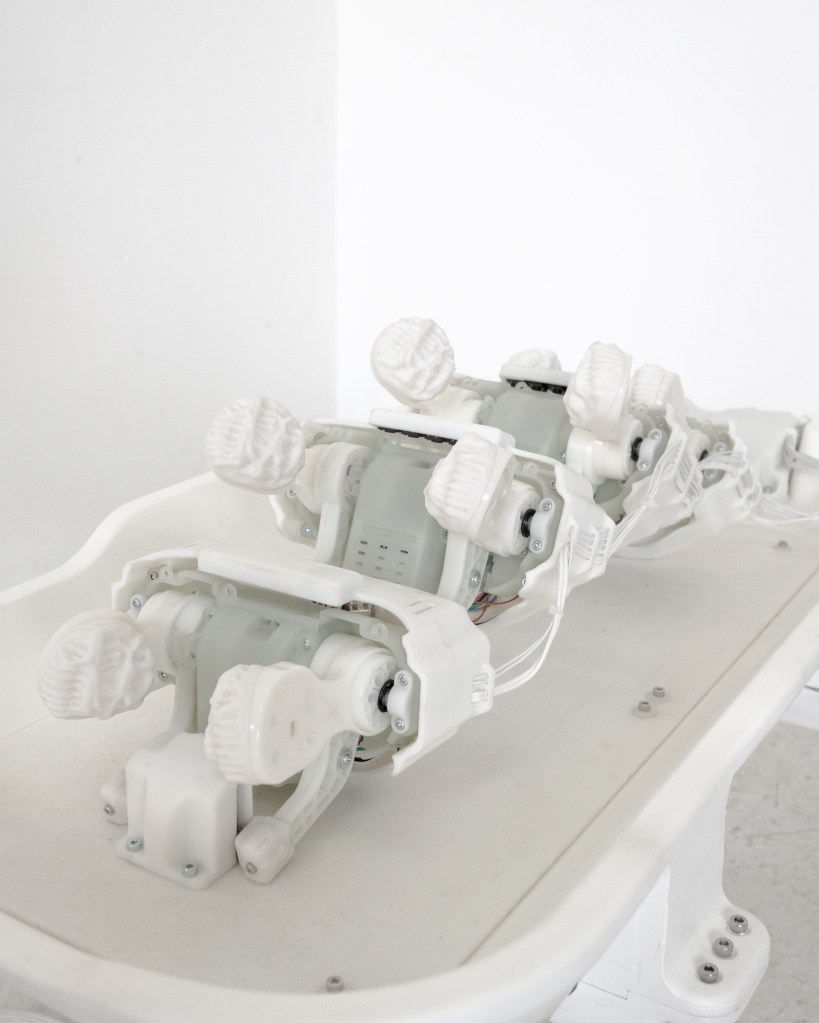

↑ Cradle-Coffin, 2024, MDF, resin (PLA), massage devices, cable, aluminium tube, arduino, office ceiling lamp 03

Marlon Nicolaisen’s work exists at the threshold between reality and fiction, engaging with themes of liminality, post-humanism, and the Uncanny Valley. Their sculptures and installations challenge our perception of objects, movement, and vitality, often blurring the lines between subject and object, machine and living being. By using digital fabrication techniques such as 3D printing and CNC milling, Nicolaisen transforms digital concepts into physical forms, creating ambiguous entities that evoke both familiarity and unease. Through their work, they invite us to reconsider how we interact with technology, the evolving role of autonomous objects, and the shifting boundaries between the human and the non-human.

Your work often explores the blurred boundaries between reality and fiction, integrating concepts such as the Uncanny Valley, liminality, and post-humanism. What draws you to these themes, and how do they influence your creative process?

New perspectives emerge right at the threshold between reality and fiction, making us see the familiar in a new light. When objects resist clear categorization and aren’t immediately recognizable, they can evoke deep emotional responses. I’m especially drawn to the idea of liminal spaces where not just individual objects, but entire environments and moments break away from the familiar, creating an in-between world. This sense of ambiguity carries a certain tension, and that’s what keeps drawing me back to it in my work.

Many of your works feature creatures and objects that exist between subject and object, questioning the perception of vitality. What role does movement play in this exploration, and how do you approach the design of these ambiguous forms?

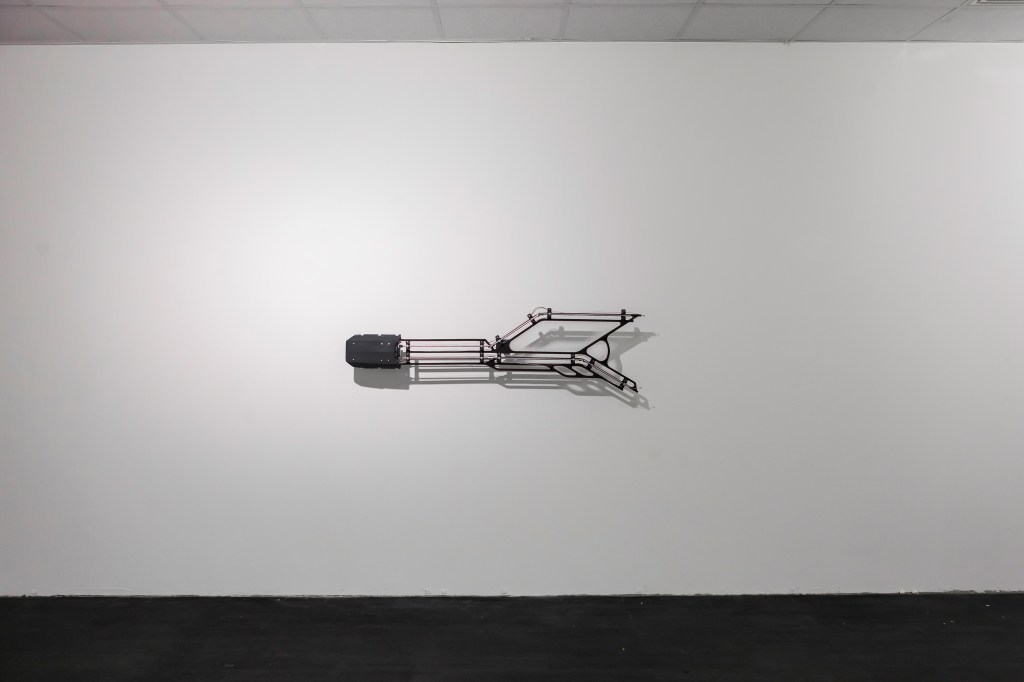

Movement plays a central role because we instinctively distinguish between machines and living beings based on the way they move. I am especially interested in challenging this immediate categorization. I try to create situations where viewers engage with an object as if it were alive—maybe even a child or an animal. But finding the right balance is tricky; I often reach a point where a piece either looks too much like a creature or too much like a machine.

Visually, I take a lot of inspiration from machines but alter their characteristics to give them a more subject-like presence. My process involves trying to understand the object as a subject. I keep asking myself: What does this object need? What should it rest on to feel soft? Does it need support? How can it avoid breaking or “hurting” itself? What could it play with? These questions come up again and again in my work. Over time, this creates a kind of relationship with the work one that can extend to the viewer, inviting them into a dialogue with the object.

Your installations often incorporate digital fabrication techniques such as 3D printing, CNC milling, and laser cutting to translate digital concepts into physical space. What challenges and possibilities do these methods offer in bringing virtual ideas into tangible form?

What fascinates me about these technologies is the level of control over shape and function. It’s an exciting process to design something digitally on a computer and then hold it physically in your hands. At the same time, it’s challenging because it often takes multiple prototypes to find the right balance between material, movement, and expression. Movement, in particular, can be tricky something that works perfectly in a digital environment might behave completely differently in the real world. But that trial-and-error process, the constant testing, refining and adjusting, is exactly what makes it so fascinating to me.

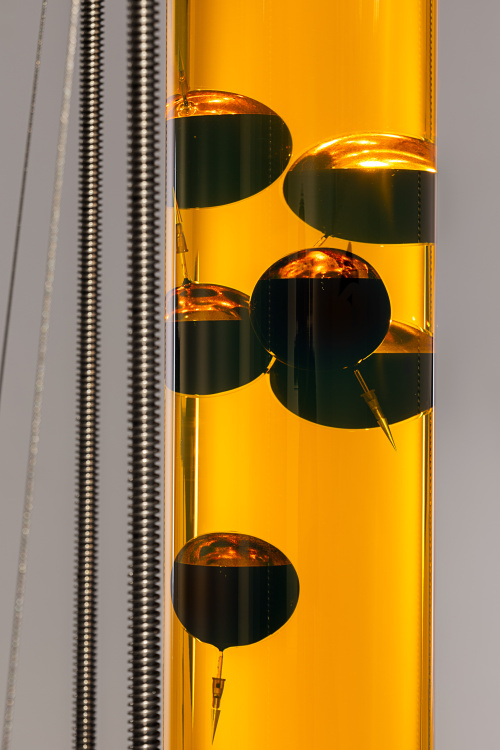

Projects like Sidequest mod: fountain and Cradle-Coffin reflect themes of transformation, life cycles, and the impact of technology on perception. How do you see your work in relation to broader discussions about the relationship between humans, objects, and technology?

My work reflects our relationship with objects and challenges how we assign meaning to them. In Cradle-Coffin, I explored the concept of the Uncanny Valley that moment when something feels both familiar and strangely alien at the same time. Today, this sense of unease isn’t just limited to human-like machines but extends to autonomous technologies that we can’t fully control.

Through my work, I want to make this shift visible: How do we interact with objects? How does our perception change as machines evolve from mere tools into seemingly independent entities? My hope is that my pieces encourage viewers to rethink these questions from new perspectives.

What do you think is the primary purpose or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

The question of a universal goal of art is difficult to answer definitively. For me, the purpose of my art is to open new perspectives and create experiences that resist simple categorisation. Through this, I aim to encourage reflection on one’s own perception and position in the world.

Art is about raising questions and establishing a relationship between the viewer and the work. Whether an object appears alive or a space generates an atmosphere that feels both familiar and alien these effects can be achieved through artistic processes. Perhaps the true purpose of art lies in this very ambiguity: not in providing clear answers, but in opening up new ways of thinking.

Marlon Nicolaisen instagram

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’25