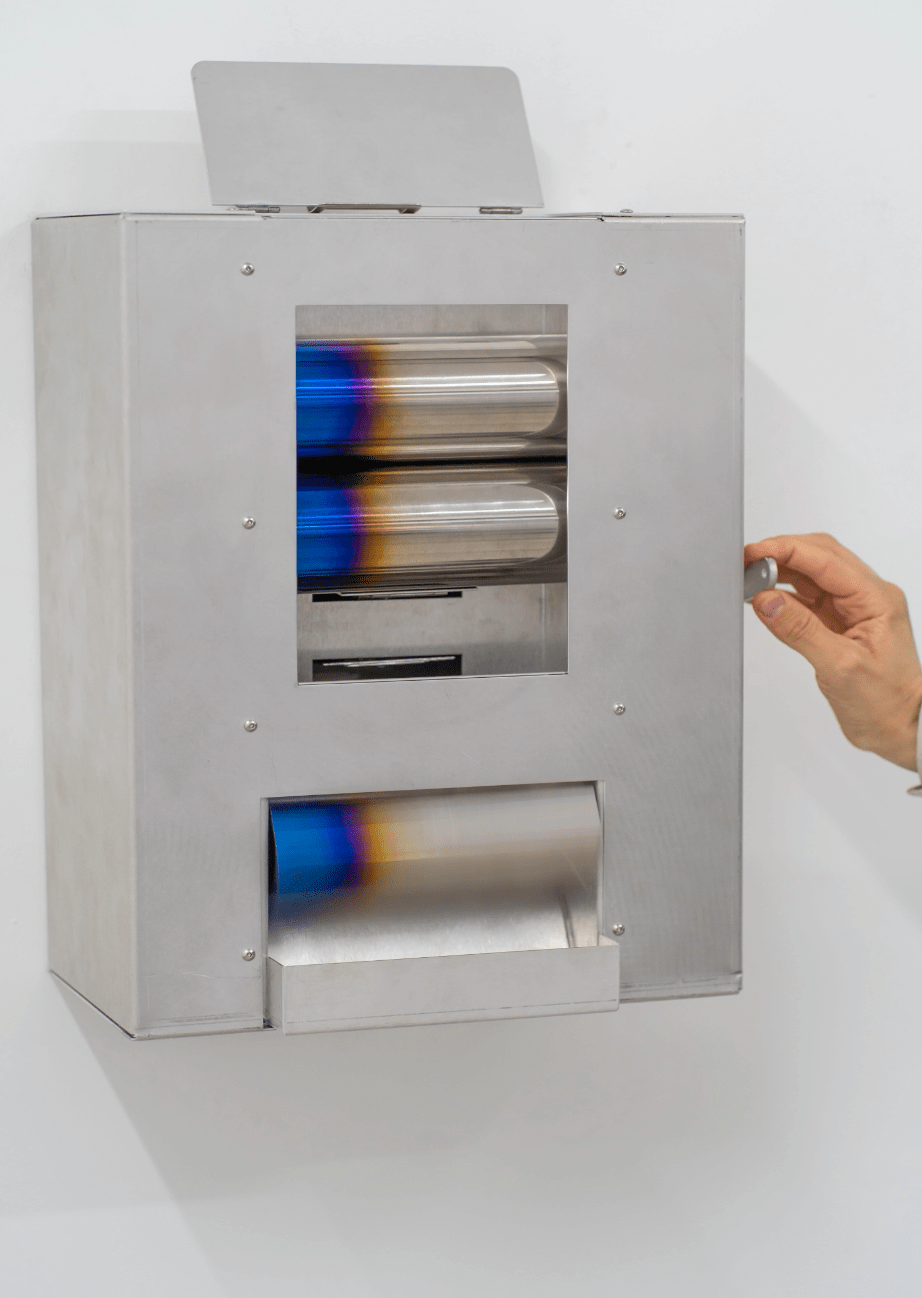

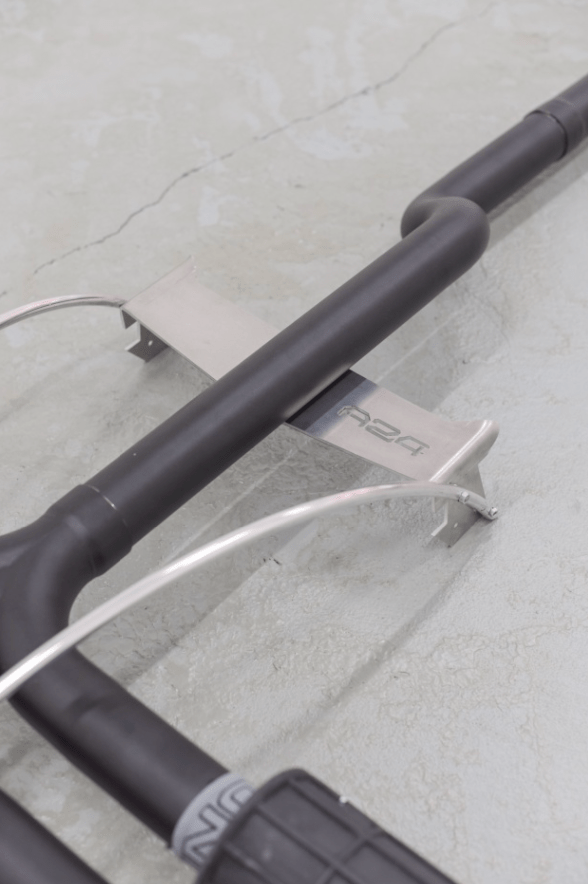

↑ Pull!-speed it up!- enjoy (2022) 60X70X20cm

Theo Papandreopoulos: Sculpting Power, Sounding Myth

Text Marie Ivanova

May 16, 2025

Theo Papandreopoulos’ sculptural world is one of raw tension—between the beast and the machine, myth and modernity, form and sound. His works stand as dense, enigmatic monuments to masculinity and its performative infrastructures. With pieces like Goliath, Attila, and Exhausthorn, Papandreopoulos confronts the industrial aesthetics of dominance—steel, horns, leather—and disrupts them with a strange tenderness, a sense of fragility hiding beneath the armour.

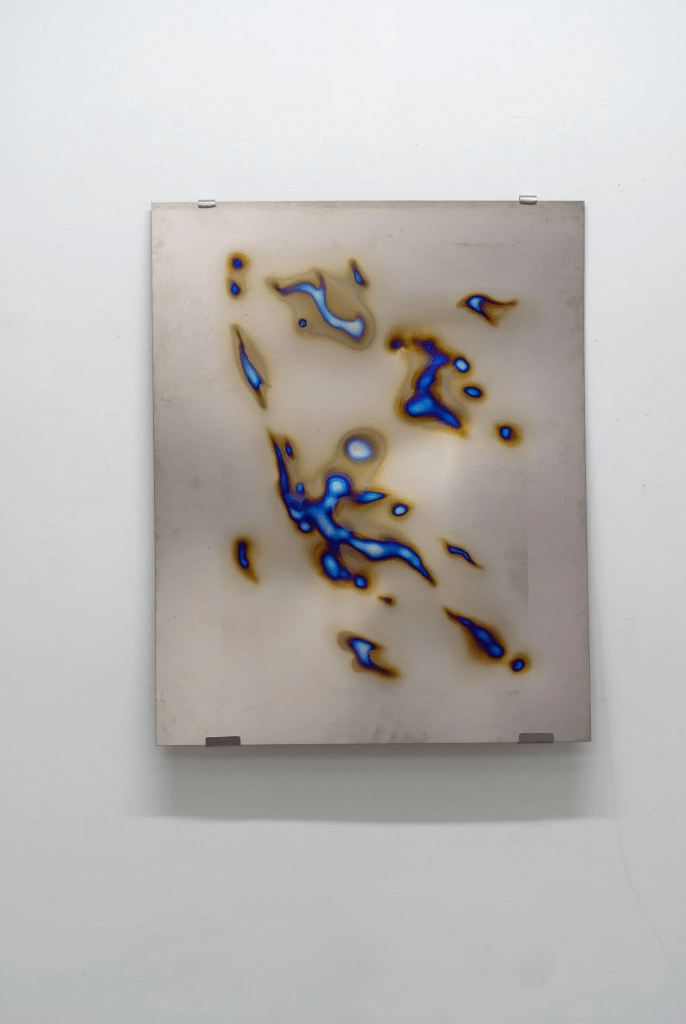

There is a ritualistic intensity to his use of materials—horns once wielded by animals, metals forged for speed and spectacle. These works are not just objects; they are artefacts from an imagined future, or ruins of a hyper-masculine present. They borrow the language of car culture, war trophies, and historical symbols of power to expose their theatricality. In Pull! Speed it up! Enjoy! the glossy surfaces and familiar mechanisms seduce, only to unravel into a parody of their own utility—strength becomes farce, performance slips into satire.

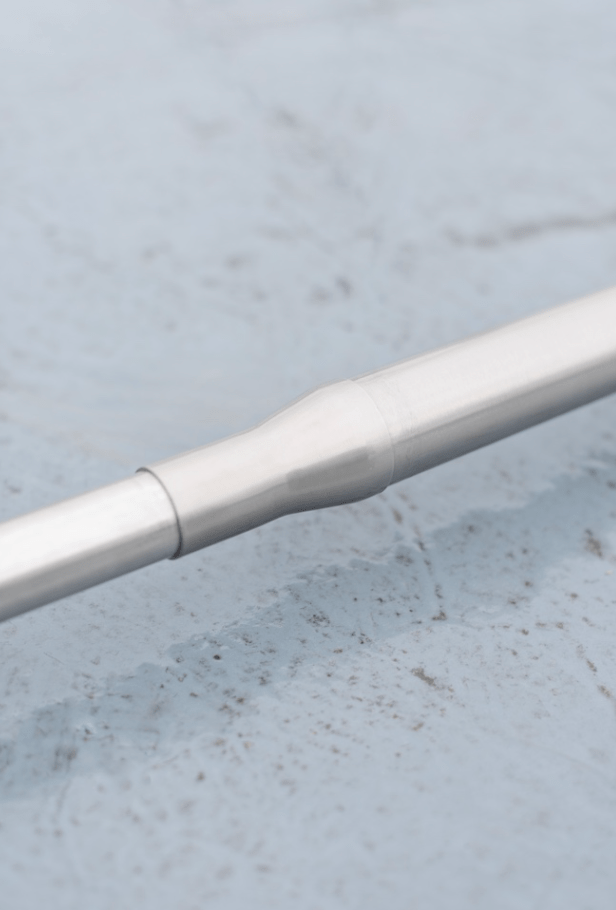

Crucially, sound is not an afterthought in this universe—it’s a continuation of form. Exhausthorn breathes life into the otherwise static, extending the sculptural experience into time and atmosphere. The work moans, growls, and resonates—an unsettling call from the hybrid beings Papandreopoulos builds. In collaboration with musician Fin Bradley, sound becomes both echo and evidence: a haunting trace of motion and memory.

The artist’s interest in symbols—from Japanese maedate to the Celtic carnyx—is not nostalgic. These references are deconstructed, reframed, and reinserted into a critique of identity construction. What happens when traditional markers of power are reimagined in the language of post-industrial fetish? The answer is neither entirely cynical nor wholly celebratory—it lies in the quiet, deliberate cracking of these icons.

Irony, in Papandreopoulos’ practice, is not light. It’s a scalpel—used with precision to carve into the overblown performances of masculinity and consumer culture. There’s humour, yes, but it’s the kind that sneaks up on you and leaves you slightly disoriented, aware of how deeply we’ve internalised the absurdity of what power looks and sounds like.

Theo Papandreopoulos doesn’t make sculptures. He builds environments where power is not only seen but felt, heard, questioned, and sometimes broken down into pieces we might, finally, begin to understand.

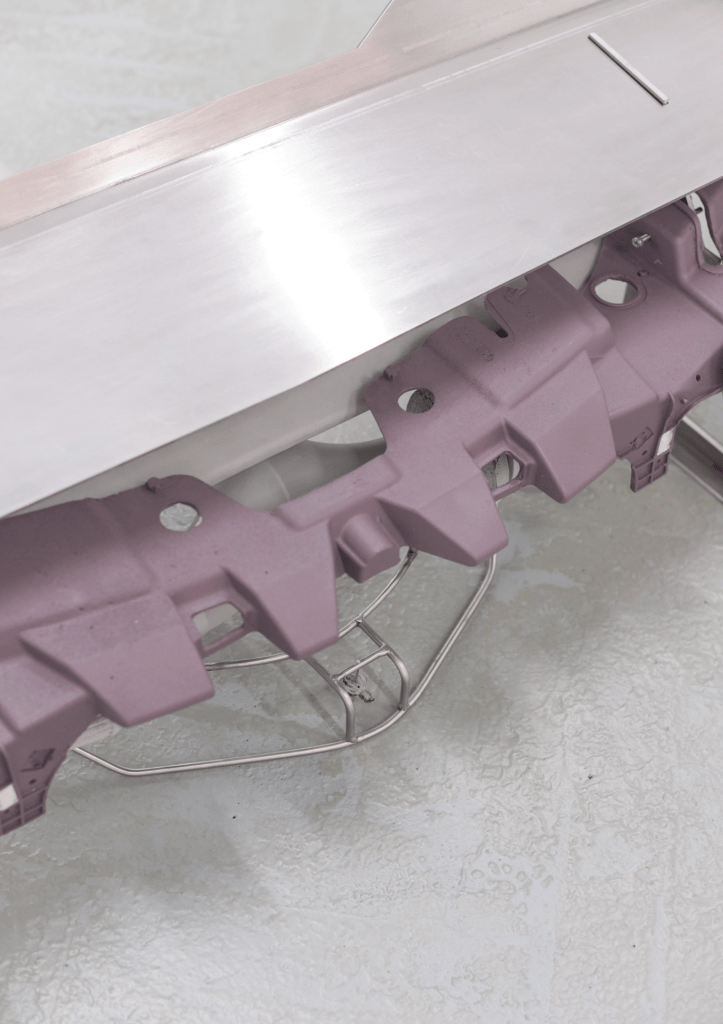

Your recent works like Goliath and Attila merge industrial materials with organic elements like horns and taxidermy, referencing power, masculinity, and speed. What drew you to this material and conceptual language, and how do you see these hybrid forms functioning within contemporary spaces?

There is something almost ritualistic about working with leather, horns, and metal — materials that once belonged to bodies or machines built for speed and domination. In Goliath and Attila, I wanted to fuse these worlds: the ancient myths of power and conquest with the mechanical language of modern industry.

These sculptures feel like relics from a future archaeology — fragments of a world obsessed with speed and strength, now corroded and transformed. By merging industrial remains with organic forms, I try to expose the fragile seams of masculinity, ambition, and technological pride.

PAUSE/FRAME By The Koppel Project, 194 The Broadway SW19 1RY

Within contemporary spaces, I see these hybrid creatures as uneasy monuments. They don’t offer a clear narrative of victory or collapse; instead, they hover in the in-between — part beast, part machine, part memory. They invite viewers to reflect on what kinds of mythologies we continue to build around power, and what might be quietly falling apart beneath the surface.

In the end, I am interested not just in the clash of materials, but in the quiet aftershock they leave behind — the question of what endures, and what is lost.

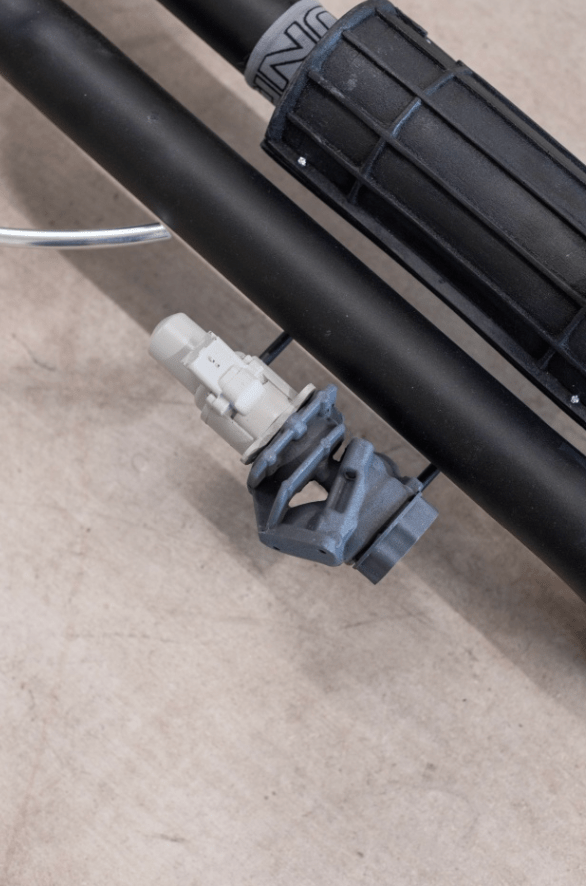

Pieces like Exhausthorn and its associated sound works add a performative, sensory dimension to your sculptures. How does sound play a role in expanding your sculptural practice, and what kind of experiences are you hoping to create for the viewer?

Sound entered my sculptural practice almost as a natural extension of the materials themselves.

Exhausthorn began as an object — a fusion of machine and beast — but I realized it was incomplete without a voice. The sound pieces are not just additions; they are extensions of the sculptures’ bodies, giving them breath, weight, a presence that moves beyond the visual.

Sound allows the work to occupy the space physically. It shifts the experience from static observation to something more embodied, something you feel through your chest and skin. I want viewers not just to see the work, but to be momentarily inside its atmosphere — to feel as if they’ve stumbled into the aftermath of a ritual, or are standing in front of something living, breathing, and slightly out of reach.

For me, sound stretches sculpture into time. It creates a rupture in the clean surfaces of a gallery, reminding us that objects, like bodies and machines, are never truly silent. They pulse, they erode, they demand to be heard.

12cm diameter(small) 32cm(big) Plaster spheres, testosterone powder

7 parts (each) 52X35X15 cm

Black polyurethane gun foam casts , rubber, metal button

CNC laser-cut aluminium, black leather, white car leather, bull horns, screws

You often reference cultural and historical motifs—from the Celtic carnyx to Japanese armour crests—in pieces like Maedate and Co-Crest. What interests you about these sources, and how do they inform your exploration of identity, masculinity, and power?

Cultural and historical motifs have always fascinated me because they compress entire worlds into forms — a single horned crest, a battle standard, a ritual mask. Objects like the Celtic Carnyx or Japanese maedate were never just decorative; they carried identity, myth, intimidation, and belonging into the world.

In pieces like Maedate and Co-Crest, I’m interested in how these symbols once defined power, how they were designed to project masculinity, resilience, or divine favor — and how fragile those constructions really are when placed under new lights.

By referencing and reworking these forms, I’m trying to explore how identity is assembled: through heritage, through projection, through fantasy. I’m also interested in how power and masculinity were—and still are—performed visually, as surfaces to be read, feared, or admired.

These historical echoes allow me to hold a mirror to contemporary constructions of identity. In a world still obsessed with strength, image, and speed, I want to ask: what happens when the symbols crack? What new forms might emerge from their ruins?

Stainless steel exhaust tubes in 3 parts, 2 stainless steel reducers, buffalo horn, polyurethane ring, screws, and mouthpiece

Works like Pull! Speed it up! Enjoy! and Muscle Balls offer a critique of consumerism, production, and masculinity through a mix of humour and confrontation. How do irony and play function in your work, especially when addressing themes of fetishisation and strength?

Irony and play are essential tools in my work because they allow difficult questions to slip past defenses. Pieces like Pull! Speed it up! Enjoy! and Muscle Balls start by seducing the viewer — with polished surfaces, exaggerated forms, familiar symbols of desire and power — but they quickly start to unravel under closer scrutiny.

I’m fascinated by how systems of consumerism and masculinity are built on performance: the performance of strength, of success, of invincibility. But those performances are often absurd when pushed to their limits — a gym machine becomes a torture device, a muscle becomes an inflatable toy.

Through humour and confrontation, I try to reveal the gaps between fantasy and reality, between fetishisation and actual vulnerability. Irony lets the work bite without becoming preachy. Play makes it possible for people to laugh at the systems they’re trapped in — and maybe, for a moment, imagine stepping outside them.

For me, humour isn’t about softness; it’s about pressure. It’s how you make cracks appear in the surface of things.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

I don’t believe that art needs a goal or a defined idea. At its core, art is driven by the instinct to imitate — to reflect life through another form — as Aristotle described, and as I deeply believe. This gesture of mimicking is not about copying reality, but about transforming it, giving it new weight, new resonance.

Behind every artwork is this basic movement: something made from something else, carrying meaning beyond itself. Art doesn’t exist to explain; it exists to let us experience. It is a tool for receiving information in a deeper, more sensory way — one that bypasses rational understanding and speaks directly to emotion, memory, and the body.

For me, art is not about offering answers or solutions. It is about holding complexity, allowing contradictions to exist, and opening a space where we can feel, reflect, and encounter meaning without needing to name it immediately.

In this way, art remains one of the most essential and human acts we have: a way of knowing the world by remaking it.

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’25