Markus Mehr: Composing the Hidden Rhythms of Ecosystems

Markus Mehr’s work stretches beyond traditional notions of composition, entering the realm of sonic sculpture—where sound becomes both material and message. In his recent project SUPRA, Mehr explores the interconnectedness of ecosystems, from lichens and fungi to urban infrastructures and black holes, using crystalline processes as a metaphor for transformation and interdependence.

Working conceptually, Mehr gathers field recordings and transforms them through meticulous processes of dissection, layering, and abstraction. His soundscapes are immersive, reflective, and often unsettling—inviting us to listen more closely to the environments we occupy and the systems we rely on.

In this interview, Markus shares insights into his process, his relationship with space and sound, and the role of art in addressing the emotional dimension of our most urgent environmental and social questions.

Your recent project, SUPRA, focuses on the interaction of crystalline processes with the help of sound. What inspired you to explore this topic and how did you translate such a complex subject into an auditory experience?

A work always begins with a concept, an intellectual exploration of a topic. The ideas for concepts can come from anywhere, there is no rule. In the case of SUPRA, it was initially about the fascination with the diversity of nature. All the lichens, mosses, fungi and trees that communicate with each other, fend off external threats, take care of each other, form alliances, etc. They form an obvious blueprint for a concept centred around super organisms. But I also wanted to consider other ‘ecosystems’. For example, the human body: a fascinating interplay of processes, mutual conditions and interactions. Or metropolises with countless interactions to keep them running. From chemical fusions to the merging of two black holes – everywhere interacting, crystalline processes that, after their transformation, produce something superordinate that is more significant than the individual elements. So I had plenty of choice to collect sounds, process them with my working methods and then assemble them into a new sound sculpture.

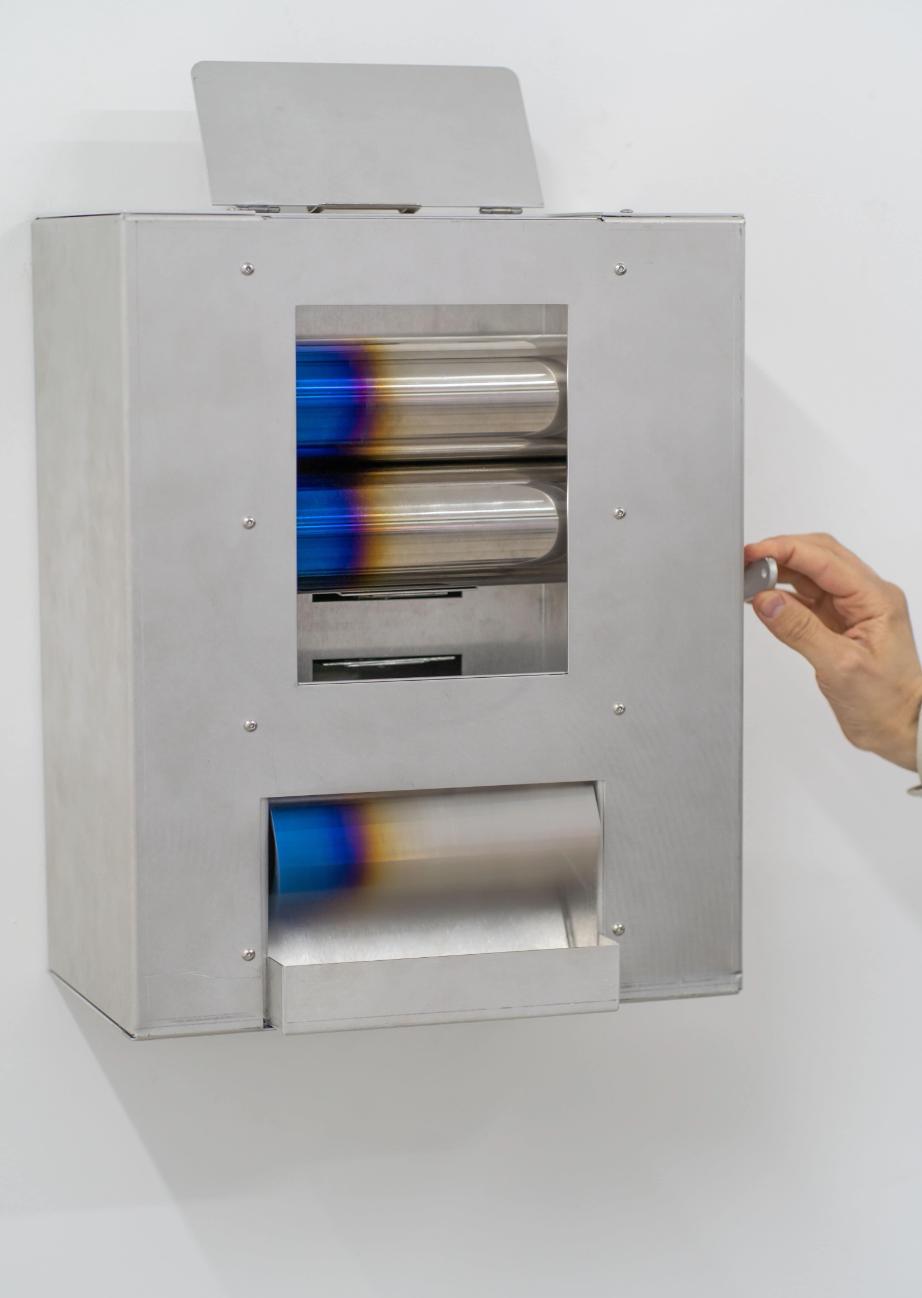

SUPRA – Sound Installation Trailer

In Brief Conversations, you focus on the acoustic properties of various spaces. How do you approach capturing the ‘voice’ of a room, and what does this reveal about our relationship with the environments we inhabit?

There were two main approaches to the recordings for Brief Conversations: firstly, to listen to the different rooms and how they produce or reproduce their own sounds and environmental sounds. And secondly, to stimulate reflections in the rooms with what was to be found in the rooms. From an ancient, broken piano on which someone was strumming, creaking plastic rubbish in tunnels to night-time visits to a church, everything was included. Most of the time, the ambient noise had a strong influence on the recordings in the various rooms. We live in a very noisy world.

Your work often involves transforming field recordings into abstract compositions. Can you walk us through your creative process from the initial recording to the final piece?

As I said, I work exclusively conceptually and in a second step I search for the corresponding field recordings. These recordings are the basic sound material, which is followed by a microscopic, dissecting process. An original sound that is broken down, enlarged, stretched, shortened, slowed down, accelerated, granulated, refined and reassembled reveals sound surprises that we do not perceive when listening to it regularly. It is exciting to distil and cultivate such sound finds from the original. Whether a sound is suitable for a loop, for a synthetic pattern, for a supporting element or only appears briefly will become clear as the composition progresses. The work then begins to take shape and goal-orientated, sometimes painful decisions have to be made: what is suitable for the composition and what is not? How do I distribute the dynamics in a sound narrative and how long can the tension be maintained? This process can take days, often months, and often ends up in the wastepaper basket. Starting from scratch.

Considering the themes of your projects, how do you perceive the role of sound art in addressing contemporary environmental and societal challenges?

Art cannot solve problems and certainly not the immense challenges we face. Art does not have answers, but questions. However, these questions are formulated from an alternative point of view, we are emotionally stimulated, thus creating other approaches. Hearing is also a highly sensitive sense. We hear in three dimensions. This fact alone offers a rich palette of possibilities to trigger us. Supra is an Atmos installation that plays with precisely this variety of possibilities. For me, art, regardless of the discipline, is the emotional complement to rational, enlightening, data-based science. Both together have the necessary power to turn the world upside down.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

If there were a goal, this would again be an earmarking, an instrumentalisation of free spirit. Art must be allowed to do everything and not have to do anything. It should be the court jester of our societies and never be apolitical, if subtly or obviously. Art invites dialogue, is open to new things, wants movement, is forward-looking. And not in a lecturing, preachy way, but in a playful, graceful, sometimes even shocking way. Art is the lubricant of our societies; if we neglect it, everything becomes arid, brittle and fragile. We should pay close attention to this.

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’25