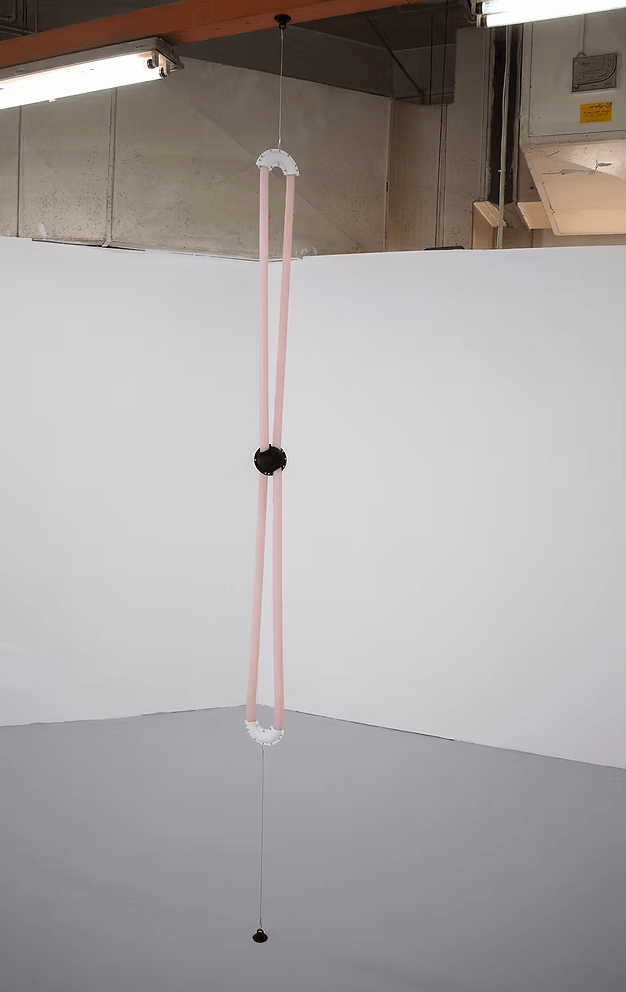

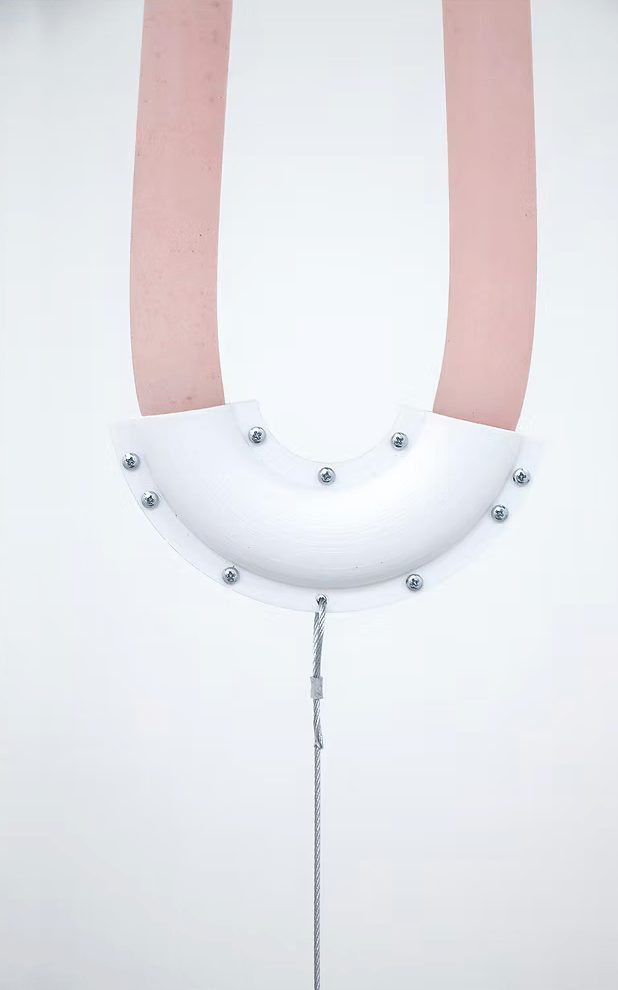

↑ Eldar Krainer, UNIFLEX, 2020, 3D print, PVC pipes, metal pipe clamps.

The Poetics of Digital Intimacy: On the Work of Eldar Krainer

Text Marie Ivanova

June 6, 2025

In a world where desire is increasingly filtered through algorithms and glossy interfaces, Eldar Krainer’s sculptural practice offers a strikingly tactile meditation on the complexities of contemporary emotion. His installations navigate the messy terrain between intimacy and performance, where identity is curated, feeling is commodified, and connection is constantly deferred.

Krainer’s work aligns with a growing wave of post-internet artists exploring how digital culture shapes our lives. But what makes his voice distinctive is his engagement with material. There is an almost archaeological quality to his sculptures, as though they are relics from a near future: part machine, part body. These hybrid objects occupy a liminal space between public and private, technological and psychological. They don’t simply reference contemporary longing—they stage it. Through scale, surface, and spatial tension, the works activate the viewer’s body in significant ways.

This comes through strongly in his piece Goodbye Letter, shown recently at Unit 1 Gallery in London. A 3D-printed heart compresses a blank note from the virtual void, forming a touching, tangible record of emotional residue. Like much of Krainer’s output, the piece is a study in contradiction—engineered yet vulnerable, offering proximity without access.

Krainer borrows from the seductive aesthetics of consumer design and digital iconography. His visual language includes references to Grindr feeds, loading animations, and gamified reward systems, reimagining them as techno-romantic props. In doing so, he draws attention to the strange mechanics of modern intimacy.

Still, his approach resists literal interpretation; its commentary unfolds intuitively. His sculptures do not ask to be understood, but to be felt. There is humour here, but it is sharp, unsettling, and tinged with sadness. Stacked pillows become bodies, a sentimental message gets inflated like a balloon, and a seemingly heavy roadblock rolls on wheels. These material deceptions echo the dissonance of digital life, where everything is real and artificial at once.

Ultimately, Krainer offers neither escape from nor resolution to the conditions he explores. Instead, he creates space for contradiction, reflection, and feeling. He invites viewers to linger in discomfort, in a landscape shaped by economic instability, code-based relationships, and the constant need to be seen.

Your sculptures often resemble industrial prototypes that evoke emotional responses. What draws you to this intersection of machinery and emotion, and how do you navigate this duality in your work?

Back in high school, I learned about Duchamp’s The Large Glass– a machine love affair, where the bachelors try to reach the bride and desire moves along an assembly line. It really stuck with me. It made me realise how mechanical intimacy can sometimes feel. This seems relevant, especially today, when emotions are increasingly mediated through screens and online platforms. I think we’ve moved past this idea of nature versus nurture. Technology is so deeply embedded in our lives that expressing emotion through something cold or industrial can feel strangely natural. There is something both alienating and oddly familiar about it.

I often like to play with those kinds of contradictions: the cold and the warm, the hard and the soft, where form holds feeling, without giving it all away. This duality becomes a way to explore how we relate to others: how much we are willing to share, and how much we keep tucked away. It’s that in-between space, where emotion and structure meet, that really drives my practice. A space to think of vulnerability in ways that might feel a bit off or unexpected, but ultimately very human.

In your piece “Sleepover,” you utilise everyday materials like used pillows and steel rods. How do these materials contribute to the narrative you’re constructing, and what significance do they hold in the context of your work?

A lot of my works have this clean, manufactured feel- minimal and a bit emotionally distant. With Sleepover, I wanted to shift things a little by bringing in found materials that feel more intimate and bodily. Pillows felt right for that. They’re deeply personal objects. They hold the shape of our heads, absorb our dreams, carry stains, smells, and traces of anxiety or comfort. They quietly witness our most vulnerable moments.

The ones I used were all old and discarded, charged with stories of their own. I liked their abject quality- messy and rejected in a way that speaks to the discomfort we often feel toward our own bodies. I sandwiched them between plastic heart shapes, held together by steel rods. Something soft and fragile wrapped in something rigid. It became a way to reflect on how we sometimes handle intimacy: wanting closeness yet staying cautious. The two pillow stacks represent two bodies. Each has different star stickers: one says “yes,” the other says “no.” It’s a nod to swipe culture, where validation and rejection are just a flick apart. What seems playful, like a pillow fight, becomes a metaphor for an emotional risk.

Your work frequently addresses themes of digital identity and the commodification of emotions, especially in the context of dating apps. How do you translate these abstract concepts into tangible sculptural forms?

On social media, everything gets flattened, turned into numbers, images, and quick slogans. It’s all so curated and impersonal, like we are constantly selling a version of ourselves that starts to feel more of the same. With dating apps, it’s even more prominent. We are promised unlimited access to love, connection, maybe even soulmates, but only if we subscribe to a premium account. There’s something so twisted in how our longing for intimacy gets monetised, like spinning reels in a slot machine.

That cycle of hope and despair is something I try to translate into physical objects. I distort the digital interfaces we usually overlook, for example, verified ticks hollowed out and turned into a ball toss game, or loading percentages paired with blurred profile pics sliding up and down scaffolding like pole dancers. It feels both familiar and altered, much like how we reshape our identities to fit the market.

These forms are like props from a digital performance- fragments of how we present ourselves online. I think the emotional dissonance sits in that gap between what these platforms promise and what they actually deliver. You’re swiping for connection, but somehow it always feels just out of reach.

Having exhibited in various international venues, how have different cultural contexts influenced your artistic practice, and are there specific experiences that have significantly impacted your work?

That’s a tricky one. Because my work often focuses on online culture, I’ve never really thought of it as being rooted in a specific place. The internet makes it feel like we are all navigating the same digital landscape. But moving to London definitely shifted things for me. Suddenly, the elements that had always informed my practice, like graffiti tags, billboard campaigns, and urban architecture, were pushed to the forefront.

Big cities have always fascinated me. There’s something about the pace, the overload of imagery, the constant need to excel or become something more. In London especially, that competitive rush of endless opportunities is everywhere- on the streets, on screens, in conversations, and it can really take a toll. I remember being struck by the ads when I first moved here. They weren’t just selling products; they were selling lifestyles- little promises of happiness or success. I had this weird physical reaction to them, like they knew exactly where to hit.

I think being surrounded by that level of consumerism has made me more alert to how easily we internalise those messages. How quickly they shape what we think we should be. That awareness has definitely seeped into the way I approach my work now.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

That’s a big question. I’m not sure I believe art needs to have a clear goal. I’ve never been drawn to the idea of utilising it for a specific cause or outcome. I think one of the most beautiful things about art is that it doesn’t have to make sense, or change the world, or even be understood. Sometimes it’s not about the audience as much as it’s about the artist, who might struggle to engage with the world in any other way.

That being said, I do see art as a form of communication. Not one that delivers answers, but one that opens up questions. It’s about challenging the things we take for granted through a kind of dialogue, sometimes with others, sometimes just with ourselves. I’m always looking for work that could move me in ways I can’t quite explain. I see art-making as a longing for that fleeting moment.

Maybe that’s the point: to create space for feeling, for reflection. Art doesn’t need to mirror reality, but it can reflect all the strange contradictions that shape us. If it makes someone pause, or think differently, or just feel a bit more, then maybe that’s enough.

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’25