Art as Process: A Conversation with Lilia Li-Mi-Yan & Katherina Sadovsky

Working at the intersection of technology, ecology, and mythology, artist duo Lilia Li-Mi-Yan and Katherina Sadovsky build worlds that are both speculative and sharply attuned to the present. From CGI and AI-assisted storytelling to site-specific installations and organic materials, their practice explores what it means to be human—now and in the future.

In this conversation, they reflect on the philosophical tensions between posthuman fantasies and ecological collapse, and how biotechnology might shift our bodies, relationships, and sense of mortality. They share their thoughts on collaboration with AI, the contradictions of synthetic and natural materials, and the emotional complexity of migration and survival after relocating to Armenia during wartime.

Through projects like Where is my plastic bag?, A000000000001000AA011 and When the hawk comes, their work questions the ideologies we inherit, the technologies we build, and the futures we are quietly rehearsing. For Li-Mi-Yan and Sadovsky, art is not a neatly defined act—it is a mode of witnessing, reimagining, and sometimes, as they put it, “putting a bullet through the head” of the narratives we’ve taken for granted.

This interview invites you into the unsettling, poetic, and necessary spaces they create.

Your collaborative practice spans a wide range of media—from CGI and AI to sculpture and site-specific installation. How does your use of emerging technologies influence the way you explore themes of posthumanism and ecological transformation?

Katherina: Technology, for us, is just new tools. AI is a limping, hallucinatory assistant. You kind of have to drag it along, keep propping it up, training it—but then, by accident, it can toss you a weird little diamond, an unimaginable string of words. We’re working a lot with text right now, so this really matters to us! New technologies definitely affect our artistic research. Simply by working—by staying inside the process—a strange, unexplored corridor opens up, and you can step in and find a new space. It’s fascinating to watch. For instance, there’s a very popular opinion now that because of LLMs (large language models—ChatGPT and the rest), people will get dumber, faster. Let’s watch! That’s interesting! Along the way, you can research, fantasize, and invent a story that might become, say, an experimental film.

Your work often raises philosophical and emotional questions about the future of human evolution. What fascinates you most about the idea of the “new human,” and how do you imagine our bodies, emotions, and relationships might shift in response to biotechnology and environmental change?

Katherina: We think that with biotech medicine, for example—a person can keep the body healthy and extend life for a while. And the environment, on the contrary, can push the body toward destruction. It’s an endless race in which the human being is both creator and destroyer. Here we mean pollution, disasters, epidemics… We probably have every chance of disappearing as a species—even with implanted microorganisms that help prevent infections by different viruses. But if we fantasise and imagine the human genome altered so radically that the body becomes adaptive to any environment, a question arises: do we remain the same humans? If you know you’ll stay relatively healthy for, say, two hundred years—what then? Do the emotional sides of life keep their value? Or do they become less valuable because of such an extended stay here? This whole system of tweaks and implantations… it will definitely do something to the brain. It’s frightening to give a person a few hundred years for pleasures. All technologies strive to defeat dying. All technologies strive to enrich their managers. Maybe we’ll end up as a successful project of brilliant engineering, so we can keep going to wars and paying taxes.

In many of your projects, there’s a strong tension between the digital and the organic—between synthetic materials and the natural world. How do you see this relationship evolving, and what role does art play in negotiating or exposing that tension?

Katherina and Lilia: What can be said about the role of art? I think it simply asks questions. We question ourselves. There is no answer. And certainly no right answer. In an ideal world, the synthetic and the natural would work together toward creation. But we don’t live in an ideal world. In art, we can use synthetic material to produce an object, for example.

In our project Where is my plastic bag? we address the meeting of synthetic polymers and the natural, collaborating with a scientist. We’re concerned with whether truly biodegradable polymers can be created and applied to replace petroleum-based ones. Nature already has ready-made polymers—starch, cellulose, silk, chitosan and chitin, proteins, rubber, RNA, and DNA. For now, it’s impossible to make a biopolymer as strong as plastic. Plastic is very cheap and wear-resistant. You can’t really quit it, because almost everything around us contains plastic.

Polymers are used not only in consumer goods but also in agriculture. Working with the lab research of the Russian scientist Sakina Zeinalova (she lives and works in Italy), we concluded that it’s possible to create biodegradable polymers from potato starch—things like flocculants for river-water purification, sorbents for wastewater treatment, and hydrogels. The hydrogel caught our attention. In agriculture, you put it into the soil, then soak it with water: it swells, fills with water, and then releases it to the plant roots over seven days. Very convenient—you don’t have to spend energy on irrigation machines and human labor every day. The problem is that most hydrogels in use now are petroleum-based and don’t degrade in soil. Thanks to Sakina’s work, we obtained a biopolymer hydrogel that shows thermoresponsive behavior; its swelling doesn’t depend on the solution’s pH. It can be cycled—absorbing and releasing water up to six times (with about a 20% decrease in swelling each cycle compared to the previous one). In soil, it degrades under the action of enzymes and mold fungi, starting around 20 days after it has entirely done its job.

The project was first realized physically at Futuro Gallery, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia. We built a large flowerbed, planted it with trees and plants, similar to a park. For almost a month, you could watch the hydrogel slowly disappear. It was a new experiment for the viewers and us. By the end of the exhibition, the hydrogel had almost completely vanished, though in some places tiny black specks remained. Perhaps in natural conditions—on a farm or in outdoor beds—it needs a bit more time to degrade fully.

Having relocated to Yerevan from Russia, how has the shift in geographical and cultural context influenced your current work? Has your understanding of connection, displacement, or survival taken on new layers since moving?

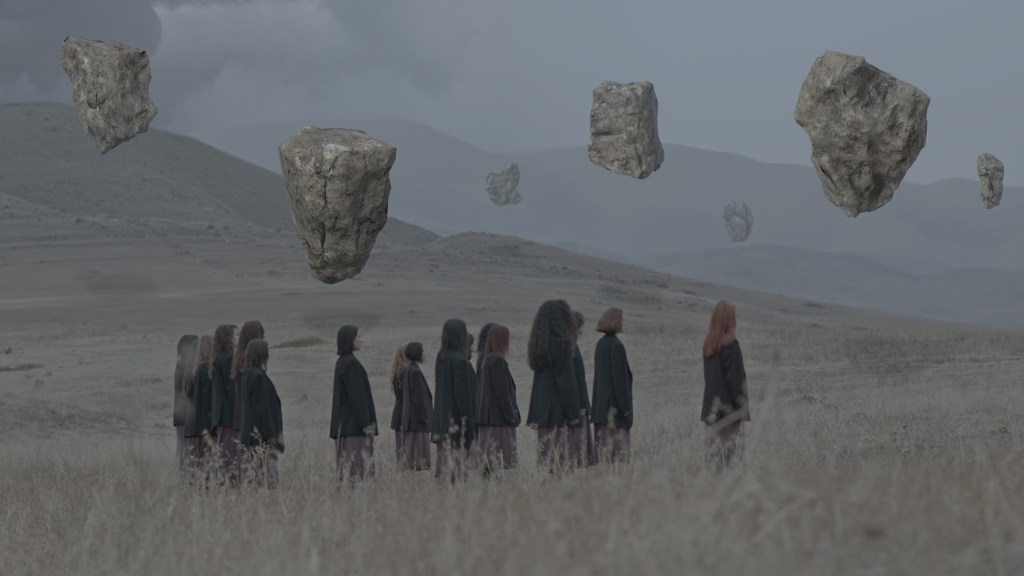

Lilia: Living between two countries turned out to be quite natural and easy for me, because I feel comfortable in both Russia and Armenia. Russia is where I lived for 30 years and became an artist. Armenia became my spiritual homeland, though I come from elsewhere. When the war began and I found myself in Armenia, my intense anxiety subsided—that space gave me support. It was there, together with Katherina, that we created a project significant to us, where we could speak to what’s happening in the world. It’s our video work When the hawk comes, based on an Armenian lullaby about a mother lulling her son to sleep. The central theme and protagonists are nineteen women (representing all women worldwide) and their war trauma. When men die in war—sons, husbands, brothers—the woman remains, but we can’t say she keeps being alive. Fear, death, violence, aggression, injustice, hatred, grief, memory—this is what stays with her. Yet the system of states keeps broadcasting the idea that women must produce new soldiers.

The video is based on an Armenian lullaby: a mother puts her son to bed, but he cries and can’t fall asleep. Different birds come to the window of his nursery and sing to lull him. Each bird symbolizes the child’s future choice—who he’ll become, which path he’ll take. The nightingale symbolizes a clergyman, the magpie—a trader. And when the last bird—the hawk—starts its warlike song, the little boy falls asleep. That means he chooses the warrior’s path. His mother cries, but accepts it.

We reconsider the force of folklore and old ideological convictions in a culture where the mother refuses to give her child to war. The lullaby runs through the entire video, reinterpreted by contemporary musicians and a choir. Nineteen women move through a desert—historically a battlefield—or are locked in a dark cave. At first glance, the landscape is boundless, yet you can’t leave it. Just as the walls of a dark temple may not be a prison but a refuge, our women are confined there, as if inside their grief.

So the themes of connection, movement, and survival gained new shades for me: they became not only personal experience but also artistic material.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

Katherina: I think the purpose of art is—to put a bullet through the head!

Lilia: I share Hegel’s view that the primary purpose of art is not so much to give pleasure as to reflect the present world—its contradictions, tensions, and searches. That’s crucial for me too: art is a way to see and show what’s happening around us today and tomorrow.

Speaking of a concrete purpose, I wouldn’t single one out. Instead, there is life itself, which we live and reflect in our works. For me, art isn’t a movement toward a preset goal; it’s a process of understanding and living through.

website limiyan.com

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition,

your Art in AOM’25 Book

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

PAI32 EDITION’25