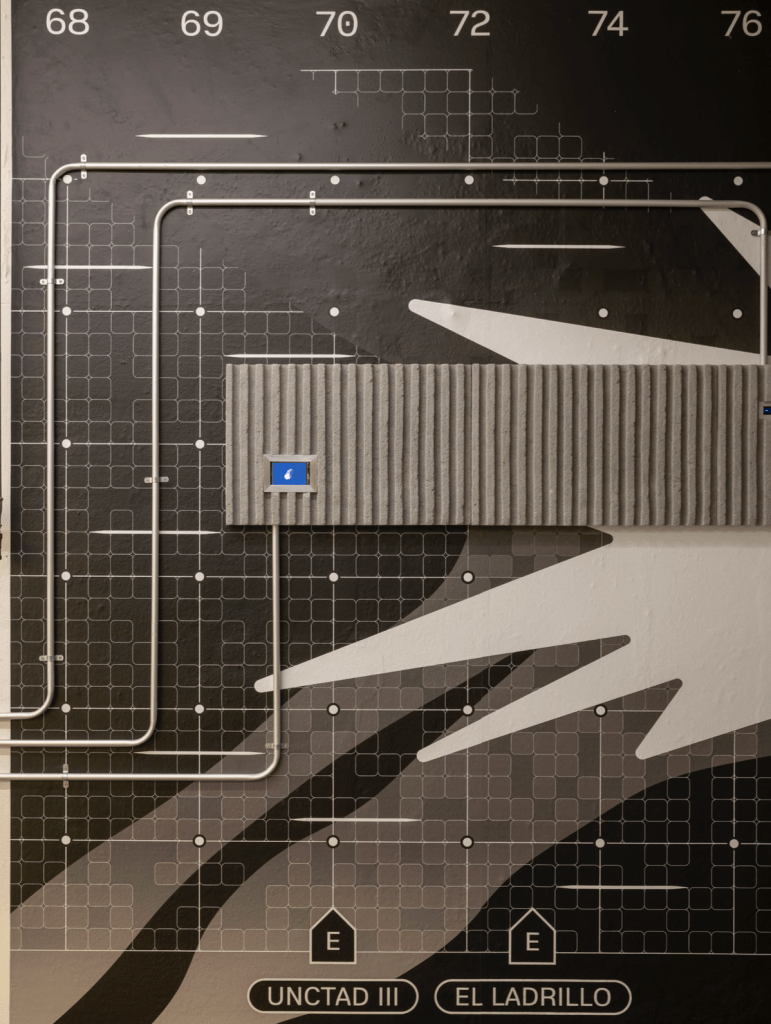

↑ El diablo va a la pega para esconderse en los escombros del presente, CAN, Neuchâtel (CH), 2023 © Sebastien Verdon

Artist Vicente Lesser Gutierrez

In his multidisciplinary practice, Vicente navigates the charged terrain of urban space—its materials, its invisible rules, its scars, and its latent possibilities for resistance. Working between Santiago and Geneva, he transforms utilitarian objects and architectural fragments into poetic devices that expose the political forces embedded in the everyday. A skate-stopper becomes a jewel. A cobblestone becomes a monument. A mirrored glass façade becomes a witness to struggle. His installations—often immersive, textual, and sonic—invite viewers not merely to observe but to confront, reinterpret, and carry fragments of the experience back into daily life.

Across contexts as diverse as public plazas, museums, and abandoned sites, Vicente’s work traces the fault lines between control and reappropriation, between state architecture and personal memory. Whether casting protest stones in aluminium or reconfiguring pyramids into inverted symbols of power, he reimagines the city as both archive and battleground. In this conversation, we explore how he translates the complexities of urban life into sculptural language, how political history becomes material, and how art can function not as a proclamation, but as an invitation to think otherwise.

Your work often explores the layers of urban space—its materials, memories, and hidden power structures. How do you begin translating such complex city dynamics into sculptural form?

A large part of my practice is based on assemblage and on diverting the primary functions of objects. My gaze in public space often turns to details that, at first glance, might seem insignificant, but that reveal power structures or, in contrast, forms of resistance. One recurring element in my work, for instance, is the skate-stopper, a device designed to prevent certain practices in public space — like skating or sleeping on a bench. These details, seemingly trivial, say a great deal about how urban space is controlled and organised. In my projects, I hijack these skate-stoppers and turn them into ornaments, transforming the object

of restriction into a jewel. Other motifs inspire me for their poetic or symbolic dimension. In Chile, for example, you often find small posters glued directly onto the sidewalks: they advertise fortune tellers, tarot services, or car rentals and sales. These everyday fragments of the city, democratic and ephemeral by nature, become writing materials for me. In several recent projects, I borrowed this format of posters glued directly on the ground to present the textual elements that accompany my installations. I’m also very interested in how state structures organise and concentrate certain populations into standardised forms of housing and urban planning. An example is the tinted and reflective glass of large buildings, which to me symbolize an architecture of power, often linked to the economic and political spheres, and to which the public and passersby usually have no access.

Starting from this detail, I created a piece based on the colorimetry of those windows: it takes the form of frames covered with mirrored film, inscribed with the testimony of a migrant woman, recounting her daily struggle in a foreign country without papers. This mirror reflects the viewer’s own image while confronting them with a very real life story, forcing them to face a reality that often remains invisible.

Finally, I also question urbanistic and architectural utopias, such as those stemming from Le Corbusier’s Athens Charter, which inspired standardized housing models. These speculative visions of the city of the future shaped contemporary urban organization, but they continue to raise questions about how we want to live together. Through my installations, I interrogate both the symbolism of these architectures and the ideals they carried, sometimes at odds with social and human realities.

© Sebastien Verdon

© Sebastien Verdon

© Sebastien Verdon

Projects like El Diablo va a la pega… and Another Gate to Llano del Rio incorporate bricks, pyramids, and symbols from Chilean political history.

How do these materials and references help you speak to themes of resistance, control, and collective memory?This pyramid was inspired by the conical ashtrays sometimes found in front of administrative

or state buildings in Geneva. They have an inverted conical shape: you put out your cigarette on the bottom of the pyramid, which struck me as highly symbolic.

The pyramid is often used as a diagram of social and economic hierarchies: at the bottom, the majority of the population; at the top, a privileged minority. The idea of diverting this everyday gesture — that of extinguishing a cigarette — seemed interesting to me. In Geneva’s typical ashtrays, you crush your cigarette “at the bottom,” symbolically on the lower classes, so I decided to reverse that logic. I designed a pyramidal ashtray where you crush your cigarette at the top of the pyramid, on the highest part of the social scale. It’s a simple gesture, but one that inverts the dynamics of power: the top, representing the economic and political elites, becomes the point of destruction.

The pyramid I made is in ceramic, a material both fragile and durable. It is slightly fractured, as if the system it represents were already cracking and slowly deteriorating.

In this piece, I also drew inspiration from science fiction and dystopian universes like Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner or George Orwell, which depict societies dominated by control and social stratification. There’s also a resonance with some of Mike Davis’s reflections on the city and its inequalities: how urban planning and architecture materialise power relations.

The piece seeks to embody a critique of social and economic hierarchies while offering a tangible, almost banal object that turns an everyday gesture into a symbolic act: the idea that the top of the pyramid — the summit of power — can also be worn down, cracked, contested.

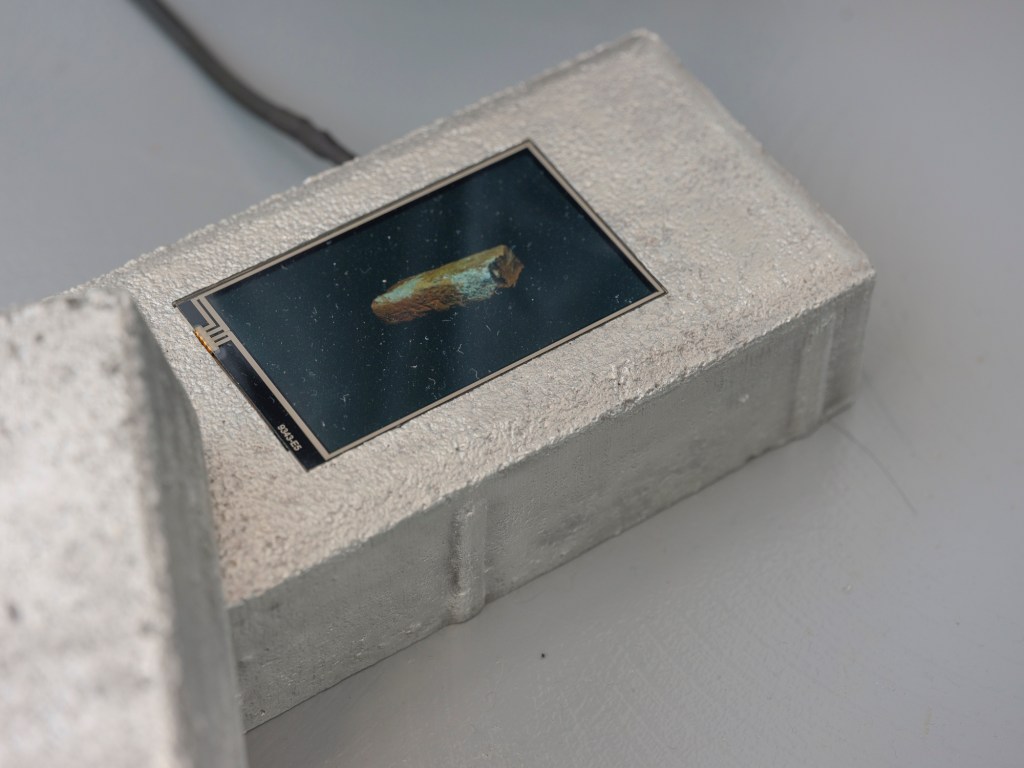

The brick is also a recurring motif in my projects. To me, it represents both the beginning of a construction and the symbol of a system. On one hand, it refers to the most basic, primary element of architecture, and on the other, in the Chilean context, to El Ladrillo (“The Brick”), the manifesto written by the Chicago Boys. These economists, trained at the monetarist Chicago School under Milton Friedman, introduced extreme, textbook neoliberalism in Chile during Pinochet’s dictatorship.

By placing the brick at the core of the installation, I bring together both the building material and the ideological manifesto that shaped the country’s political and social organisation to this day.

In the installation, the brick takes on an almost retro-futuristic dimension, with a cyberpunk aesthetic. As if, in a near future, neoliberalism itself reached its limits and eventually collapsed, causing a profound fracture in the system. The screens embedded in the bricks then become artefacts of a gone past, remnants of an economic order that dominated the world but inevitably disintegrated.

I inserted brick videos into fragments of Chilean paving stones, as a response to the systemic violence of neoliberalism. These paving stones have been a recurring tool of protest in Chile: torn from the ground and used as a means of defence against authority. I chose to melt them into aluminium, a material found both in construction and in urban furniture, to turn them into relics. By transforming these cobblestones into cast-metal objects, I give them a status of recognition, much like the bronze statues that populate public space.

Traditional statues almost always represent figures of power: soldiers, colonizers, leaders, philosophers… They tell the official story of the city and pay tribute to an elite. By giving cobblestones – symbols of social uprising and popular revolt – the same kind of sculptural treatment, I reverse that hierarchy and question who is entitled to memory and recognition in public space.

You’ve created site-specific installations across Santiago, Geneva, Basel, and beyond. How do different urban and social contexts shape your

approach to each new project? Do you adapt your methodology based on place, or is it rooted in a consistent conceptual framework?

I think it’s always important to contextualise the work, whether in relation to a site’s architecture, its history, or the country’s historical context. Having lived in two different countries and carrying two cultures within me, I also try to reflect on how my work dialogues with these different realities.

One approach I’ve developed is a methodology of contextualization, often through text. I try to weave together a historical situation tied to the place (the city, the country, the specific site) with a personal story. It’s a way of building a bridge between the intimate, the political and the collective.

I also try to produce works in which viewers can reappropriate certain fragments – a piece of text, a gesture, or a situation from a performance. This allows them to enter the work and find resonances with their own experience, rather than simply observing it from afar. In my practice, whether through architecture, sound, or text, it has always seemed essential to situate the artistic gesture in a precise context: the place, its story, its inhabitants. Sometimes it transforms into an immersive dimension, which is an important element of my work.

Your installations often integrate sound, video, and public interaction, blurring the boundaries between art object and lived experience. What role does audience participation—or the public’s physical presence—play in completing your work?

I don’t know if the spectator plays a “particular” role in my work, but their presence is always important. They are often confronted with two ways of interacting with the installation: seeing the piece and reading a text or listening to a sound. Sometimes the experience becomes fully immersive, as in the project Basamento, where body, space, and sound converge to create a more direct and sensorial experience.

What I particularly like is the idea that each person can take something away: a fragment of a story heard through speakers, a memory, a suspended moment. Once they return home, whether it’s a text, a sculpture, a gesture, or a particular atmosphere, I hope the experience continues to resonate. The nature of that resonance, positive or negative, doesn’t matter much to me; what counts is that the person carries something with them, a small piece of the work that accompanies them afterward.

For me, it’s this intimate reappropriation, this bridge between the installation and everyday life, that truly completes the work. The piece doesn’t exist only in the exhibition space: it lives on in the memories, sensations, and thoughts of those who have encountered it.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

I try to bring and propose a reflection that is neither didactic nor frontal, like journalism or documentary, but instead to offer interpretive keys that each person can complete on their own. I believe the impact is much stronger when those keys are not fully given, when each person is invited to finish the reflection in their own way. In the art world, it’s about observing and reflecting on approaches from new perspectives, shedding light on ways of seeing and understanding that we are not used to experiencing.

How do artists address issues like racism, migration, memory, or history in their practice? Each one tackles these questions in their own singular way. I seek to reveal unexpected angles, those that escape habitual perceptions. The goal is not to simplify or conclude, but to open up a space for reflection and experience.

A work can be revelatory and stir diverse emotions : it can be beautiful, sad, unjust, or horrible. Its interpretation remains entirely subjective, but the essential thing is to generate movement: to allow each person to evolve, to question their certainties, and not to remain stuck in preconceived perceptions. It’s in this exploration and openness that art can truly transform how we see and inhabit the world.

Artist website vicentelesser.ch

Credits for the images :

1. La Mochila Pesada, Tiers Lieu, Genève (CH), 2025, © Dylan Perrenoud

2. El Diablo va a la Pega, Instituto Telearte, Santiago (CL), 2024, © Paulina Mellado

3. El diablo va a la pega para esconderse en los escombros del presente, CAN, Neuchâtel (CH), 2023 © Sebastien Verdon

4. Wastes shall be stored at the top of the pyramid, Palazzina, Basel (CH), 2023, © Finn Curry

5. Another gate to Llano del Rio, Museum Langmatt, Baden (CH), 2023, © Severin Bigler

6. Invisibilidades, CALM, Lausanne (CH), 2022, ©Laura Morier-Genoud

7. NEXO, Villa Bernasconi, Genève (CH), 2022, © Dylan Perrenoud

8. Basamento, Maison St-Gervais, Genève (CH), 2021, © Vicente Lesser9. A large space allows you to (…), Swiss Art Awards, Basel (CH), 2021, © Guadalupe Ruiz

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition

#artist of the month

On Writing, Translation, and the Material Life of Emotion

PAI32 EDITION’25