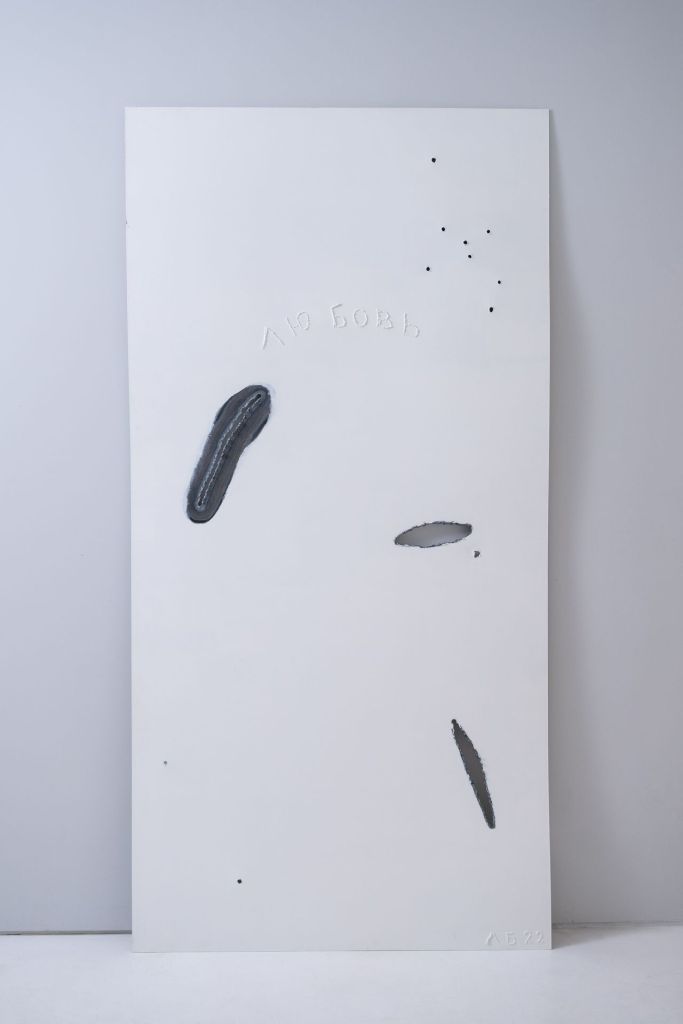

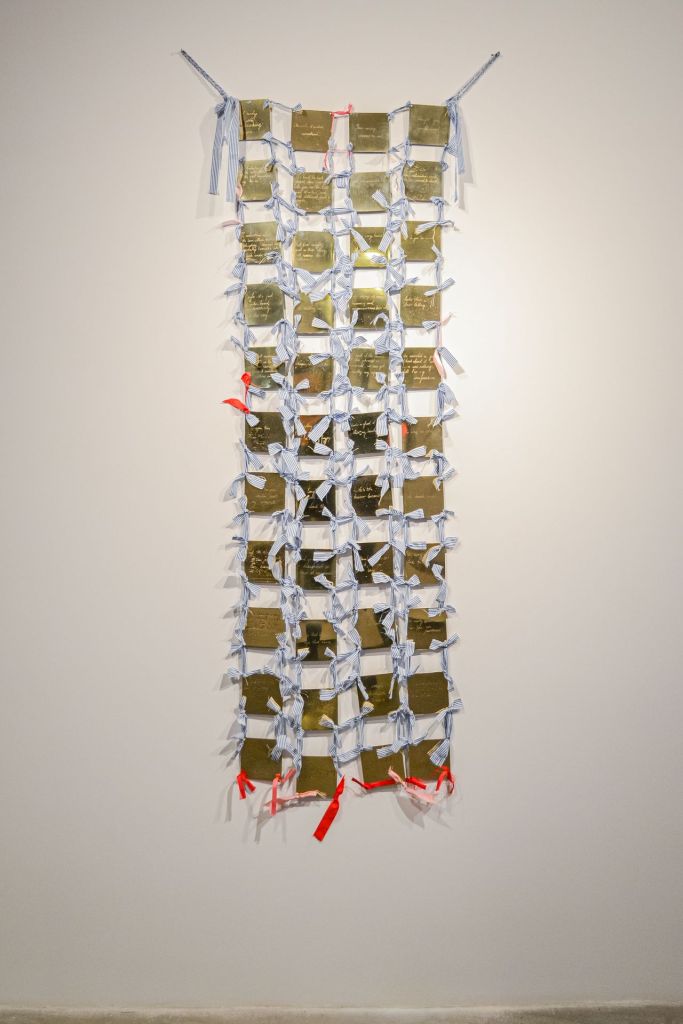

↑ Gesture slightly stuck, 2021

Artist Liza Bobkova

In the work of Liza Bobkova, sound is not merely something to be heard — it is an event, a gesture, a state of becoming. Tracing speech patterns, recording fragments of human hesitation, or translating voice into drawing, she approaches sound not as a static phenomenon but as pure duration, inseparable from life itself. Her longstanding relationship with stutter — an interruption that fractures both speaking and listening — led her to investigate the mystery of “perfect delivery,” and eventually expanded into a broader obsession: how do we capture the vitality of sound as it unfolds, trembles, collapses, or recovers?

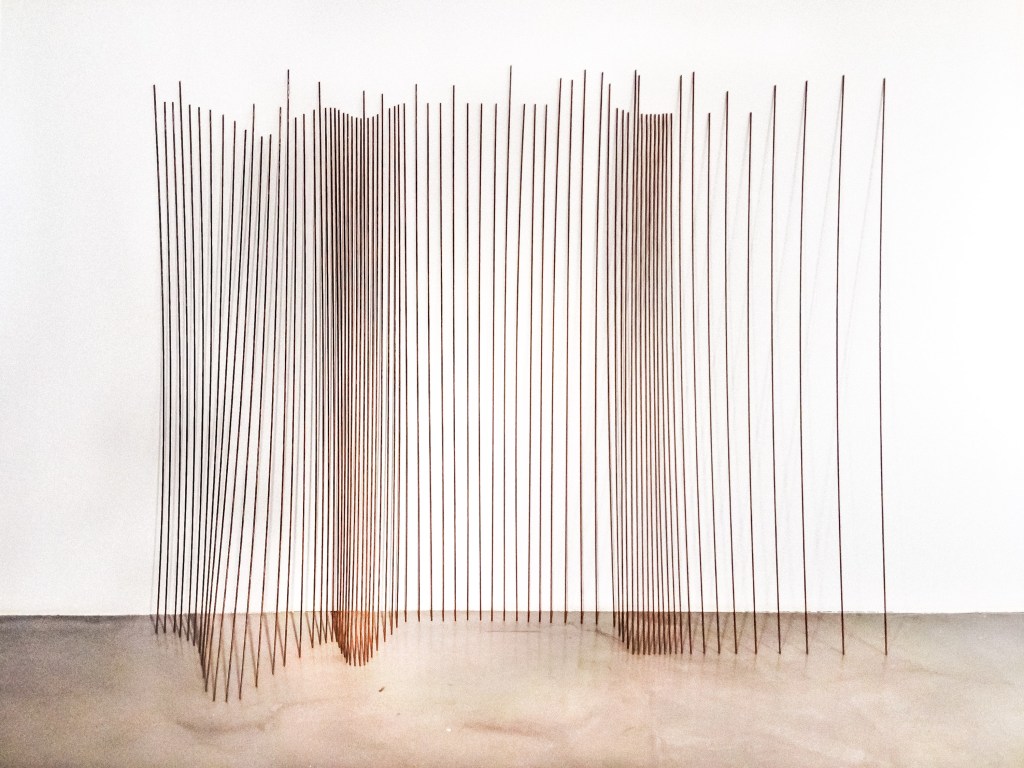

Her practice extends beyond listening. She invites us to play with sculpture as we might have as children — rolling balls across a floor, repositioning metal rods, reshaping gestures in real time. For Bobkova, sculpture is not something to be observed at a distance; it must be touched, configured, disturbed. The artwork is never finished until someone else — viewer, gallerist, collector — joins in. She rejects the pedestal in favor of shared ground.

What emerges from her reflections is a radical proposition: art as a site of unguarded sincerity, where exchange happens not through rhetoric or spectacle, but through unexpected acts of trust. Whether whispering into a dictaphone or quietly rearranging objects, Bobkova composes spaces where human vulnerability and curiosity can coexist — without expectation, without transaction.

In this conversation, we explore how she listens to the world, how she draws what cannot be seen, and why for her, sculpture remains “like playing in a children’s sandbox.”

Your work captures transient, unfiltered moments through sound — from everyday noise to the rhythm of human speech. What initially drew you to sound as a material, and what does it reveal for you that other mediums might not?

Sound is duration, it is movement — it cannot be static, like a stone lying in a field. Sound only exists in action, whether active or passive, and for me that is an essential marker of vitality. Since childhood I’ve had a stutter, which has a peculiar quality: when an episode begins mid-speech, you become absorbed in the breakdown itself, you forget what you were trying to say, you lose the thread of the conversation, and even listening collapses as a function. This made me want to unravel the enigma of perfectly delivered speech, of harmonious or chaotic sound as it unfolds. Over time, this almost obsessive attentiveness expanded to encompass all sounds.

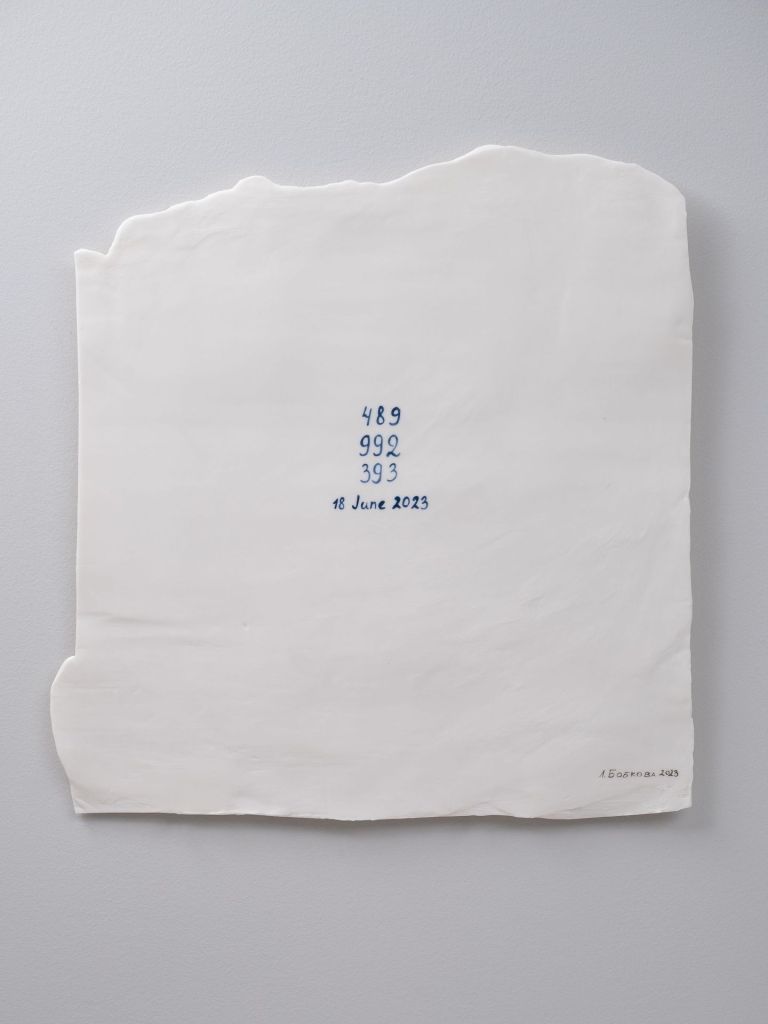

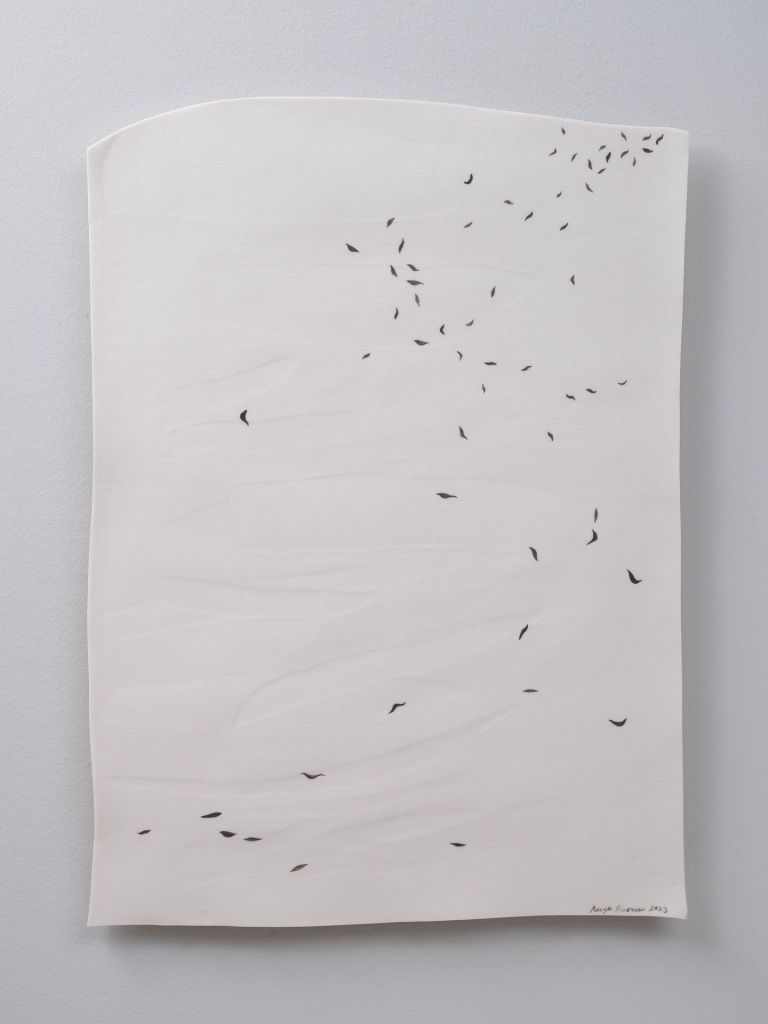

The process of hand-drawing sound waves transforms fleeting auditory moments into visual, almost sculptural forms. What does this act of translation — from voice to waveform to drawing — mean to you artistically and conceptually?

For me, it recalls the act of documenting a witness statement — a reminder that we are still human: that we feel, notice, regret, falter, and find ways to recover. By recording phrases on a dictaphone and then drawing the sound waves of those phrases — words that once existed as fleeting chat messages — I reanimate what has nearly slipped away in the endless scroll of daily life. I’m compelled by the idea of capturing sound’s movement, of documenting its unfolding in time. And the fact that these drawings are not formed arbitrarily by the artist’s imagination, but are shaped by the human organs of speech themselves, makes them feel even more vital.

You describe sculpture as a “gesture” capable of transformation within space. How do you conceive of the relationship between your sculptural forms and the viewer’s physical presence within an installation?

Perhaps because of a lack of live exchange, I am always searching for kindred spirits willing to play with me. I try to create conditions in which the viewer feels compelled to respond. It’s not work that belongs to mass entertainment — rather, I see each piece as a kind of riddle, one that can only be solved in the encounter between two poles: artist and viewer, “+” and “–.”

As a child this play took the form of hide-and-seek or tag. Today it manifests as metal spheres rolling across the floor, or aluminum rods leaning against the wall for hours. My accomplices are the viewers who move the spheres, the gallerists who open space for transformation, or the collectors who commit to teaching future generations how to reconfigure my rods into unexpected forms.

I long ago abandoned the pedestal; I brought sculpture down to the same ground on which our feet stand. My works are conceived as transformative — their potential only reveals itself in each new configuration, and that requires the viewer’s physical presence. A “gesture,” as I understand it, is a statement extended through space — and all these elements allow that statement to continue evolving.

Hand rolled porcelain, bronze with etching, ART4 Gallery, London, UK

Hand rolled porcelain, bronze with etching, ART4 Gallery, London, UK

Hand rolled porcelain, bronze with etching, ART4 Gallery, London, UK

Your installations aim to become “sites for exchange.” What kind of exchange are you hoping to facilitate — and how do you see this dialogue unfolding between the artwork, the space, and the audience?

The most valuable form of exchange, for me, is unplanned sincerity. It is a rare treasure to witness someone step out of their fortifications — and to allow myself to do the same. Not through rehearsed slogans, but by being, even for a moment, emotionally unguarded. “Unguarded” for me means being willing to play someone else’s intellectual game according to their rules, within a buffer zone of trust where nothing is demanded in return — no service, no money, no post or repost.

Put simply, sculpture is like playing in a children’s sandbox.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

I believe the central idea of art is that it offers a free space for posing the questions that have always preoccupied humanity: how to be, and what to do?

Its purpose, as I see it, is to remind us to remain human, to act as individuals, to discover new knowledge, and to learn to voice our own perspectives. Ultimately, to find personal freedom.

Artist website lizabobkova.com

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition

#artist of the month

PAI32 EDITION’25