Between Skin and Circuit: Rethinking Human–Machine Entanglements

In a world increasingly mediated by digital systems, artist Timon Bohn invites us to pause and consider the infrastructures beneath the surface—not just the networks of cables, memory chips, and electromagnetic waves, but the ways these systems shape our bodies, senses, and identities.

From tattoo machines that etch data into skin to performances that transform outdated RAM chips into living storage devices, his work is a visceral negotiation between flesh and technology. The body becomes not only the site of contact but the medium itself—recording, decaying, and revealing the fragility within even the most “advanced” systems. In this interview, the artist reflects on how cables become form, how voltage becomes performance, and how the supposedly immaterial world of digital life is always rooted in the physical—rare earths, human labour, and skin-deep memory. He reminds us that technology is not something separate from us, but something we build, shape, and are shaped by—again and again.

You often begin with a fascination for a specific electronic component or technological phenomenon. What draws you to these elements, and how do you decide which ones to explore in your work?

Yes, indeed, at first there’s always a certain kind of curiosity. I like to explore the foundational or rudimentary aspects of the highly complex computerised systems that constantly surround us. By breaking these systems down into fragments, those components reveal themselves to me. For example, in the work Entangled Body Infrastructures, we use a memory chip (RAM) that due to its outdated properties, is easily accessible. By simply providing or denying voltage, the memory gets manually written with 0s and 1s. In order to do that, Julia and I came up with a physical interface: a series of jacks positioned in front of our torsos, enabling us to write the memory by plugging and unplugging cables into them. This very performative engagement, with what a RAM is and test its limits, simultaneously clarifies and demystifies technology for me.

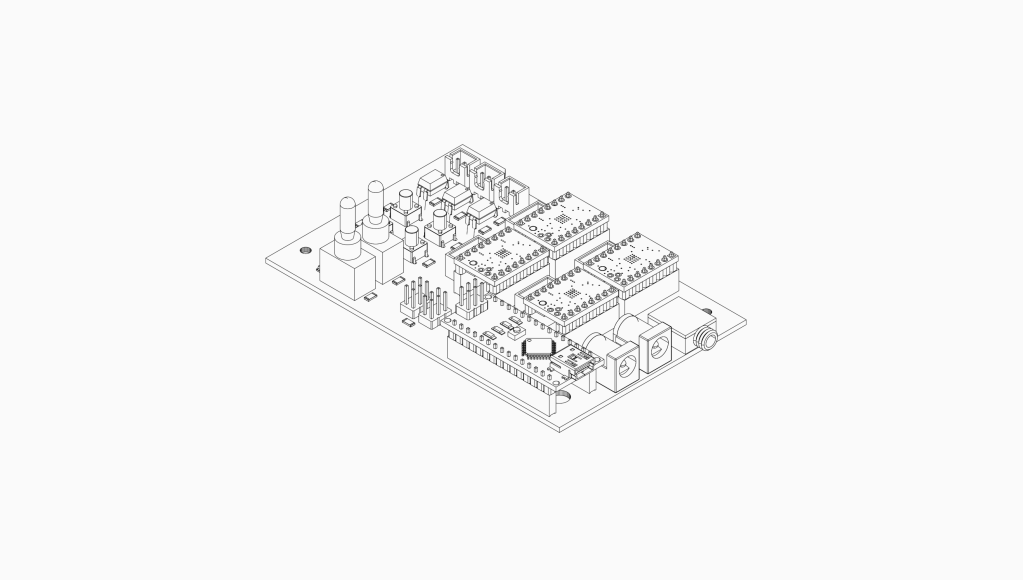

“Garden of forking paths is an installation making use of the physical connection between electrical resistance and heat. A matrix of printed circuit boards forms the canvas for a dendritic maze. Designed algorithmically, the maze reproduces naturally occurring structures, reminding of meandering rivers or winding surfaces found in organic life.

In a delicate negotiation, proximity, distance and the length of the maze’s paths need to be carefully balanced in order to result in electrical resistance and heat. On the other side, a thermochromic surface will block the view in colder areas, while allowing for a deeper glance into the maze where heat opens a window. A fluid display that reveals and hides, transforms constantly and invites contemplation on growth and entanglement.”

You mention that “what makes us human is our interdependency with technology.” In a time when technology often feels alienating or opaque, how does your work invite viewers to renegotiate their relationship with it?

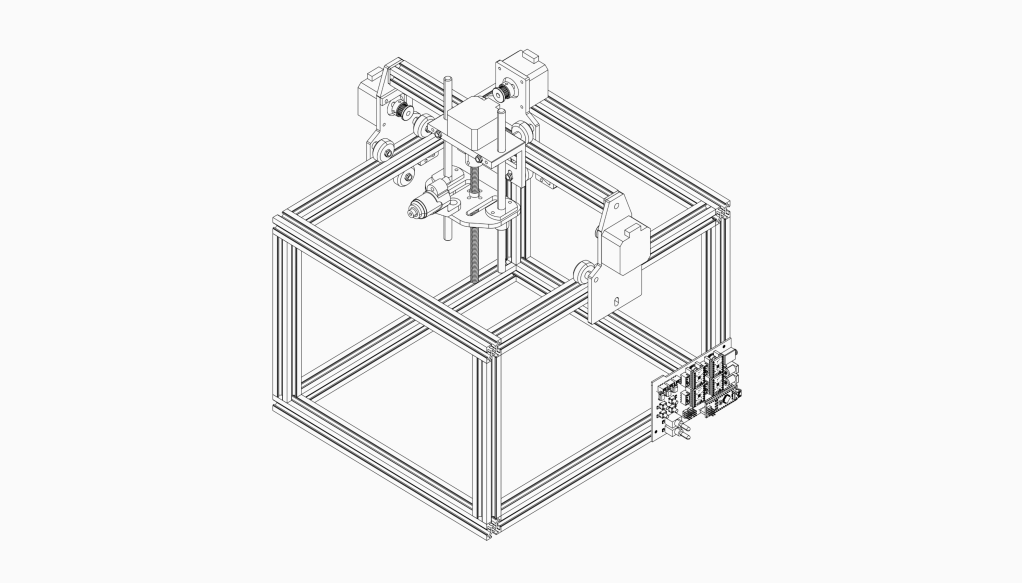

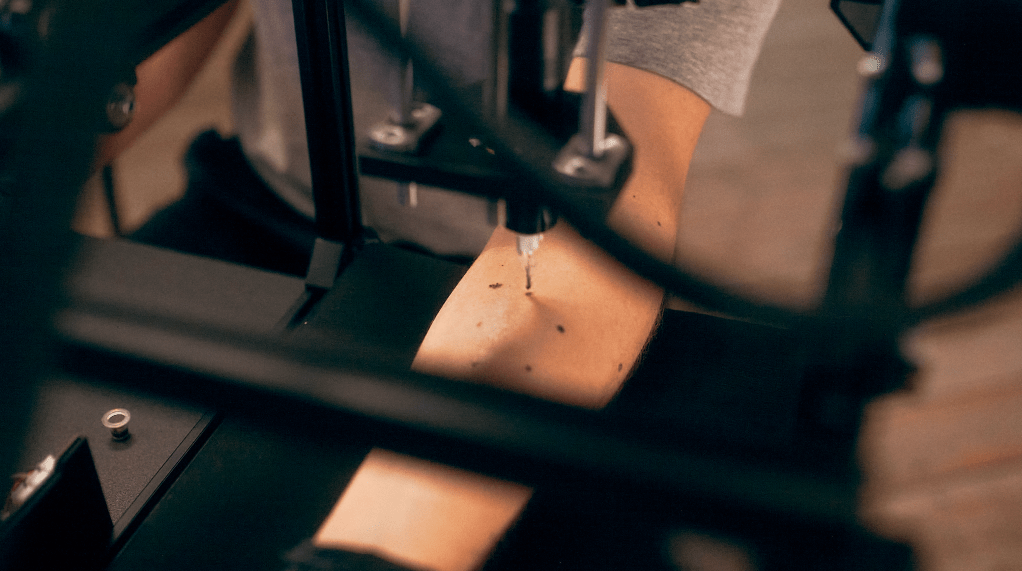

Humans don’t just invent tools and then that’s it. Whatever we invent, we’re fundamentally shaped and changed as a species by it. One could say that humans therefore (re-)create themselves through incremental adaptations, extensions, through a continuous dialogue with artifacts, through design and technology. I became aware of this intertwined approach to our relationship with technology through the writings of historians Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley. One work in which I negotiate this relationship is wo das ich sich entscheidet. For this performance I built a machine, that tattoos – essentially pierces – my body. As I’m the designer and the user of the machine, the delicate task to pierce right just under the surface of my skin is a constant readjustment between the apparatus and me. In the process of development, I, the designer and the apparatus shaped each other. The assemblage of the machine became an intimate encounter between human and artefact – a humbling process of (co-)creation. When performing the work, the audience experiences this encounter live. The moment the needle approaches my skin just enough to almost touch, a certain intimate moment is shared with the audience. Even though the machine might pierce through my skin, it is not per se invasive, rather a negotiation. For a moment my surface opens to the needle – I expose both my body and the machine. And again it contrasts all the mystical notions ascribed to technology. Because the setup is completely visible to the audience, the machine’s workings are rudimentary and transparent. Everyone can relate to the sensation of their skin being pierced and imagine what it feels like.

Your practice seeks to re-situate the human body within digital and technological infrastructures. How do you approach creating a tangible, bodily experience of systems that are typically invisible or abstract?

The intertwining of my works with my body creates like a projection surface for the human-machine entanglement. I don’t create interactive works for the audience to engage with directly. But I trust this projection surface as a vehicle for the audience to witness the bodily experience, as in the work I mentioned above. My body becomes the surface to understand certain functionalities, like the storage for example. When the ink is successfully injected under my skin, information of location, movement and depth of the needle are saved underneath. Thus, the

moment of contact between the apparatus and myself is irreversibly inscribed into my skin. It is stored. Just as media storage decays over time by being read or by the fact that its physical components naturally degrade, the stored information on my skin will too. Just like stored information, a tattoo seems everlasting, but they’re not. Over time both decay, get corrupted and fade. Even in my installations, when my body is absent, the body and its senses are still at centre. In electromagnetic unheimlich for example, I situate the body into an urban soundscape. The antennas work like an expansion to the body making electromagnetic waves audible.

Visual elements like circuit boards, cables, and connectors appear frequently in your work — not just as function, but as form. How do you see the aesthetic and poetic potential of these infrastructural components?

Instead of hiding these components they become the gestalt of the work. I find it important to bear in mind, that what we call the virtual space, heavily relies on rare earths, natural resources and human labor – each bit transferred or processed is not immaterial, there is no digital without the physical. That’s why for me, it’s essential to not only reveal these elements, but to put them at centre. They manifest the literal transportation of information. Cables are the very foundation of

global interconnectedness. Take internet infrastructures for example, just the last meters to our smartphones and computers are wireless. The majority of critical traffic is backed through hundreds of kilometre long fiber-optic cables on land and undersea, shaping local conditions and geopolitics, while also being shaped by them. Cables thus reveal relations. Between individuals and between powers. The space between sender and receiver is material. This might be one of the reasons why cables are a frequently recurring image in my work. Why I don’t like to reduce cables to their mere functionality, but instead play with their aesthetic potential.

“Through five antennas, this installation dives into the signification of urban soundscapes. Each antenna receptive to electromagnetic fields, captures different atmospheric events in the Very low frequency (VFL) radio band.

The video shows a field recording of the setup on top of an apartment complex in Athens. With its vast landscapes of receiving and transmitting antennas, it becomes an intriguing environment for electromagnetic listening.”

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

I don’t necessarily think in terms of an aim, but rather the space a work offers both the artist and their audience to explore, (re-)negotiate or (re-)evaluate. It’s fascinating to observe how each artist develops their own toolkit and language through which to work and contribute to the discipline, always deciding which aspects of a work to bring into focus. For me this toolkit includes breaking down technologies, collecting references, understanding interdependencies, playing with

aesthetics, experimenting with electronics and algorithms, building new tools, and more. It’s a space where I can continually grow and fuel my curiosity.

Artists website timonbohn.net

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition

#artist of the month

PAI32 EDITION’25