↑ Windmill House, 2023 Wood, silver leaf, stain 27 x 17 x 4 cm

Hugo Suchet: Sculpting Time, Energy, and Imagined Futures

Blending architectural logic with poetic speculation, French artist Hugo Suchet creates sculptural works that sit delicately between deep history and imagined future. From silver-leaf bas-reliefs to wind-powered botanical machines, his practice is rooted in ancient craft traditions while probing the technological and ecological anxieties of our time.

Suchet’s work doesn’t just propose alternative energy systems—it invites us to reflect on the symbolic, spiritual, and material roles that objects and infrastructures play in our lives. Whether through the slow carving of wood or the speculative logic of “anemobotanic” ecosystems, his sculptures ask: what do we carry from the past, and what are we building for the future?

In this interview, Hugo shares his thoughts on sacred geometry, low-tech futures, ecological imagination, and why art might be less about answers and more about closing the distance between the world’s beauty and our ability to feel it.

Your work often merges ancient forms with renewable energy technologies—like wind turbines sculpted in wood or enshrined in silver leaf bas-reliefs. What draws you to this intersection of the archaic and the futuristic, and what dialogue are you sparking between these temporalities?

The most advanced technologies are still developed with the aim of understanding the most common natural phenomena. Some of these phenomena were understood—though not yet scientifically explained—by archaic civilisations that used them daily to live, craft and heal. In today’s pursuit of sobriety, what we call low-tech, drawn from archaic forms of knowledge, is not a set of outdated habits but a genuine horizon for the practices of the future that will be hybrids of low and very high techs. In the imaginary spaces I am trying to create the archaic and the futuristic are not seen as opposites, but as coexisting realities.

Bas-relief is a technique rich with historical and sacred associations. What led you to adopt this form as a central part of your practice, and how do you see its role in re-enchanting contemporary objects?

The sacred dimension of an object of worship is closely related to the cultural and spiritual value of an artwork. It is not the cost of the materials used to make a Christian cross that gives it its sacred quality, but its symbolism, its peculiar geometry. Likewise, the value of an artwork is not defined by its physical properties, but by its place within art history. The bas-relief technique carries an entire sacred lineage, which I find meaningful to reinvest through a contemporary practice, as a way to extend what was once an instinctive form of art.

Carving a rough, resistant material also demands patience and a tangible sense of “deep time,” something increasingly missing from Western societies overwhelmed by their own accelerationism. This exercise can also be considered as an ode to slowness.

45 x 40 x 4 cm

In your ‘Anemobotanic’ series, fictional wind-powered plants emerge like fossils from burned wood. Can you share more about how this series came to life—and what it says about extinction, adaptation, and the ecological imagination?

The idea behind the Anemobotanic series comes from a concept used in biotechnology research that I find fascinating: the possibility of replacing combustion engines with metabolic machines. This idea goes far beyond “clean” renewable energy. By using the naturally functioning chemistry of living cells, these systems can produce energy without being consumed in the process — the material is simply transformed through the ordinary activity of living organisms.

Imagine vast, specialised flower fields swaying in the wind to generate the energy we need ; or gigantic forests becoming living data centers using the Wood Wide Web. It offers a poetic way to approach one of the major challenges of our time.

140 x 78 x 3 cm

37 x 21 x 4 cm

21 x 17 x 3 cm

23 x 23 x 4 cm

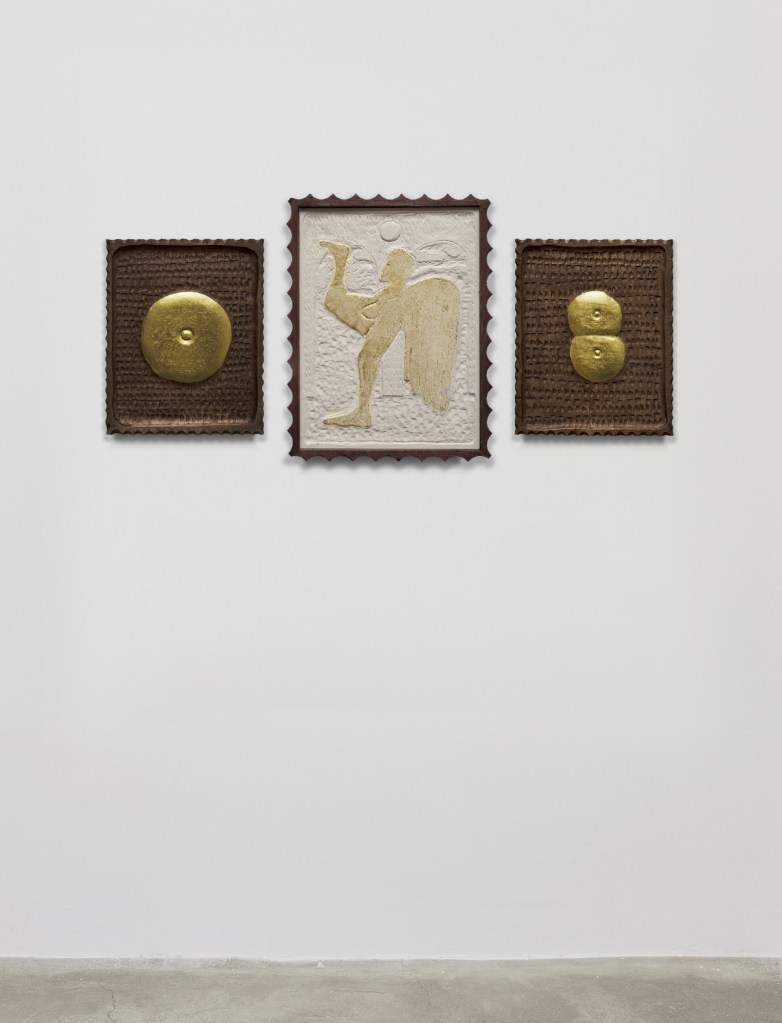

Gold painting on wood 27 x 22 x 3 cm

You describe your practice as being rooted in architecture yet infused with a symbolic, almost spiritual dimension. How has your training as an architect shaped your approach to sculpture and environmental thinking?

An architectural edifice is made to endure. It hosts life for decades and should outlive its designers. Building, therefore, is an act entwined with the notions of life and death, inviting a certain humility when confronted with the brevity of our own existence. From my perspective, architecture is not only functional but also communicative, educational and symbolic.

The symbolism that was gradually abandoned with the rise of modernist philosophy now reappears in contemporary forms, although these often operate more as decorative motifs than as meaningful symbols carrying narrative and depth. I believe that, when they are genuinely meaningful, symbols are a powerful way to bring people together around a shared imaginary — one that can open alternatives to individualistic thinking. A symbol is not a brand, it is a shared story that connects us to our history and to shared values.

This is the way I try to summon symbols in my practice: to invest images with a depth that is now threatened by new generative technologies, which produce signs without signification.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

Art is something that a priori was commanded by no specific natural forces or physiological needs, yet it appears with the first humans and in every culture on Earth, making it something inherent of our human condition. I don’t know if art has a goal, but I am assuming that art is created to fill a void, a distance between the beauty of the world and the ability that humans have to see it. We are all mesmerised by a sunrise, but we feel this beauty outside of our body, external to us, art is maybe what helps us to bring a bit of this beauty inside our souls.

Hugo Suchet website hugosuchet.com

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition

#artist of the month

PAI32 EDITION’25