Sculpting Time, Pressure, and Decay

Working at the intersection of industry and nature, New York-based artist Vadim Kondakov creates sculptural forms that breathe, corrode, and evolve. Through hydroforming, oxidation, and electrochemical layering, his metal works don’t just hold form—they hold time. His practice embraces decay not as destruction, but as transformation, revealing the inner life of materials often considered cold or lifeless.

With a background shaped by both industrial environments and academic training, Kondakov’s move to New York prompted a new sensitivity to context, scale, and impermanence. From large-scale outdoor installations to fragile oxide transfers on paper, his work explores what it means to collaborate with materials rather than control them.

In this interview, Vadim speaks about working with pressure (both literal and metaphorical), his fascination with the living behaviour of metals, and why he sees art as a catalyst for thought rather than a tool for answers. His sculptures invite us to slow down and witness material change—not as loss, but as meaning.

Your work often involves hydro-forming and manipulation of metals, letting water and corrosion shape form. Could you share what initially drew you to this process-driven approach, where nature (water, oxidation) and industry (metal, welding) meet — and how you balance control and chance in those transformations?

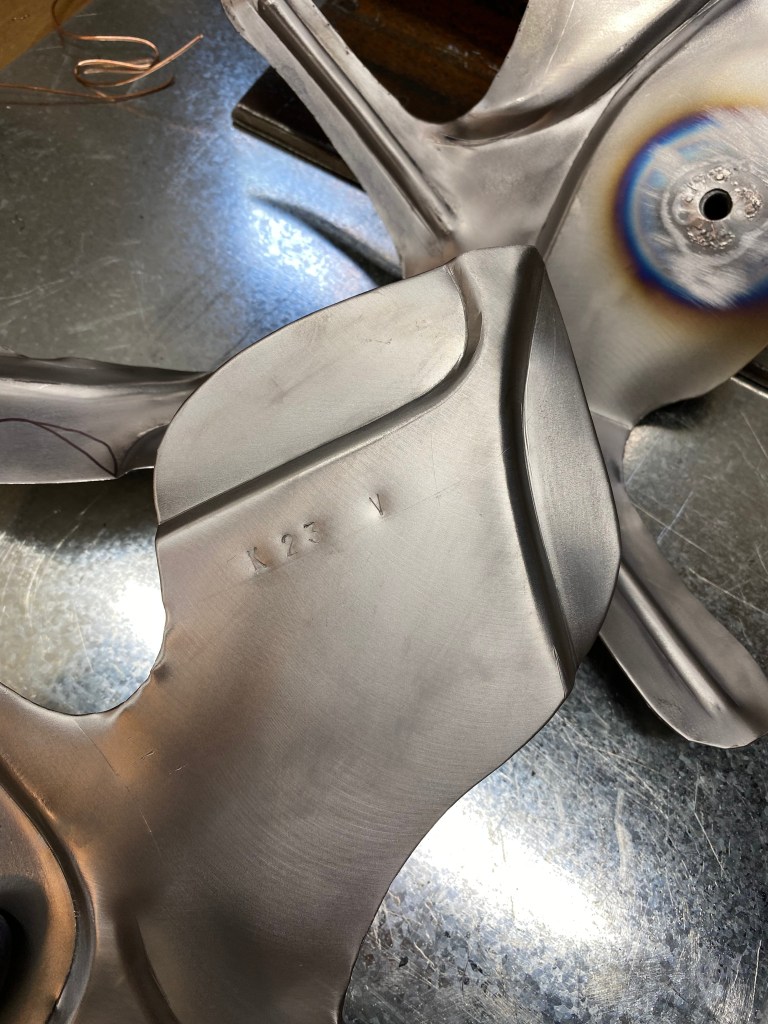

First and foremost, I am always interested in experiments. They give me the freedom to think and observe living processes. My next interest lies in the properties of materials and the manifestation of their natural logic of behaviour, and their interactions in a shared environment. In the course of my experiments I consider materials that I work with as my equal counterparts, their properties being part of the overall equation of creating an artwork. I like to feel the freedom of materials, to see art in co-authorship, in collaboration with them. Metal, a powerful blast of water creating space inside a flat steel shape, or textiles that absorb oxides in close contact with metal, and even the environment where the object is produced, can all be called co-authors. Behind the scenes, as a rule, there are a couple of unknowns, too, resulting in an unpredictable number of variations of the end result. Within this collaboration, we all share a common property: every element of this game is under pressure, quite literally. And the process we all go through gradually reduces each other’s tension upon arriving at the end result.

Many of your sculptures and graphic prints explore the tension between industrial materials and organic processes — between permanence and decay. What does this interplay mean to you in terms of time, memory, and human labour?

The industrial approach to materiality seeks to preserve objects by keeping their material properties unchanged. To protect mechanisms and structures from decay, in a sense, means to extinguish life of the material, halt its natural cycles, but to preserve the object, the product. I am, on the contrary, interested in creating objects that demonstrate the natural properties of their materials, thus creating a semantic tension between human labour, ecology, and the museumification of artistic and natural processes.

Recently, I began covering steel objects with copper through an electrochemical process. For steel, this layer becomes an additional reagent, since traces of acids left after the process, continue to oxidise the steel surface underneath copper film. At the same time, the steel corrodes from the inside after water was used to expand the object. Such sculptures are very sensitive to air humidity and room temperatures. They behave like living organisms—a very fascinating sight. They continue morphing over time, which is an inherent idea of these works, and traditional conservation would be inappropriate here. Rather, it is my invitation to witness the transformations of these objects.

Hollow inside, my objects appear as vessels, and their empty inner spaces serve as spaces for reflection. This is reflection about time, including the question, until what point will these inner interiors be hidden from the viewer. Or, who is the viewer if we talk in terms of geological time? And the more unpredictable and complex the conditions of this problem, the more interesting it is. Such a vessel can be filled with many questions, just like any work of art. I am not aiming at finding the answers. They are very difficult to find. The more multifaceted and mysterious art is, the more it resembles the truth, in my opinion.

Your background includes training at academies and working in industrial‑town environments, and now you’re based in New York. How have your personal history and changes in geographical context influenced your artistic outlook, especially regarding themes of labour, industry, and environmental impact?

Upon moving to New York City, for many reasons, I had to rethink the approach to my work. It was a difficult period, but nevertheless useful and necessary. New York is a bubbling broth that is constantly boiling, and you can feel its intoxicating vapours even if you are recluse in your studio on Staten Island, or somewhere in New Jersey. My artistic and culinary instincts continue to make endless attempts to throw my own ingredient into the boiling mass. It is very important for an artist to feel the taste of their own dish and to distinguish the nuances of another culture in it. Even in your native place, it is important to think about this and keep your attention focused on trying to synergise the creative process with the local context.

The steel oxides in the city are reminiscent of metal returning to its ore state. I like how the port city has turned abandoned piers into parks and well-designed promenades. In New York, I really like Socrates Park, which was built on a former landfill and is now an art residency for artists working with sculpture and the environment. Sculptural parks in upstate are impressive with their scale, often also offering great art residency programs.

The change in context prompted my series of objects New Layer. In it, I introduce additional layers to metal objects either physically or chemically. In a way, it reflects accretion of my own cultural experiences. Pragmatically, these objects are often small scale—produced of scraps of my large-scale objects, a kind of recycling,—which makes them easily portable, nomadic in a way. There is a large piece within this series, too,— Level Tree sitting on the slope of Cary Hill sculptural park in Salem, NY. Its production process connected me with the local community, its shape is very site-specific, and the different types of metal I layered within this piece make it weather and morph over time.

Beyond sculpture, you also create graphic works by transferring oxide films from metal to paper or textile, producing delicate prints that contrast with heavy- metal origins. How do you think about this shift in scale and material — from heavy industrial metal to fragile paper — and what does it reveal to you (and you hope to reveal to the viewer) about transformation, fragility, and impermanence?

My mother worked for a company where they drew special graphs based on seismic surveys to locate oil deposits in the earth’s layers for extraction. As a child, I perceived those graphs—cross-sections of the earth drawn by a computer in the form of thin coloured threads, winding on a huge sheet of paper, in which I could wrap myself completely—like waves of water or growth rings of a tree. They gave me some failed printouts to use as drawing paper when my mum took me to her work. And I remember that if you dripped water on them, all these mysterious threads would blur into a beautiful rainbow-coloured stream.

When as an adult I started working with metal, I once accidentally left a sculpture wrapped inside a plastic bag unattended for a long period of time. It was one of my first experiments with metal inflated with high water pressure. At the time of its creation, it seemed uninteresting to me, and I forgot about it for a long time. Finding it a year later, I barely managed to unwrap it, tearing off pieces of the bag in which it was wrapped.

There I discovered beautiful patterns of rust. I realised that this was metal’s manifestation in a new form. The steel, oxidising, had been transferred to the surface of another object. It had become part of another material. I began collecting scraps from my own sculptures and stacking them in small piles, interleaving them with sheets of paper and sometimes fabric. Then came the ritual of adding life-giving moisture—water. And patiently waiting for the result. I was immersed in this process, just as if in meditation. The sheets of fabric and paper with rusty imprints would transform into freely undulating waves. This visual language showed me the connection between the transitional states of the material and the life of the object created of it. In other words, as steel corrodes, it partially transitions to its primary state of ore. In a way, this completes its life cycle.

What do you think is the primary idea or goal of art in general? If there is a specific goal, what would it be?

Art for me is a process of manifesting life. It helps to illuminate something that otherwise is not seen in the ordinary. Like a reagent, art reacts with human senses, breaks mental boundaries, sparks the process of thinking, and acts as a catalyst for the movement of thoughts and ideas. The power of this movement can change things and, eventually, transform the world. Sometimes it seems that art is powerless, and it is impossible to change the world by it alone.

The world art history does not change people; they remain wild and unreceptive. But art does not have to teach, just to prompt us to ask constant questions about the world. Perhaps its transformational power depends on the concentration of active substances in art. If a lot of energy is invested in it, then the return will be commensurate.

Website vadimstudio.art

ARTIST OF THE MONTH

Interview, Online Exhibition

#artist of the month

PAI32 EDITION’25