↑ NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM/ UNIVERSITY OF GOTHENBURG

A brittlestar found on the seafloor of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone

Deep-Sea Mining Test Shows Heavy Damage to Seabed Life, Study Finds

Machines used to test deep-sea mining in the Pacific Ocean have caused substantial harm to animals living on the seafloor, according to the largest study of its kind.

Scientists found that in the tracks left by mining vehicles, the number of small animals was 37% lower than in nearby undisturbed areas. Species diversity also dropped by almost a third.

The research team documented more than 4,000 animals on the seabed in the Clarion–Clipperton Zone, a vast area of the Pacific between Hawaii and Mexico. Strikingly, around 90% of those species had never been recorded before, underlining how little is known about deep-ocean life.

This region holds huge quantities of polymathic nodules rich in nickel, cobalt and copper – materials central to technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles. But plans to mine these resources in international waters are highly contentious and currently not allowed until the environmental consequences are better understood.

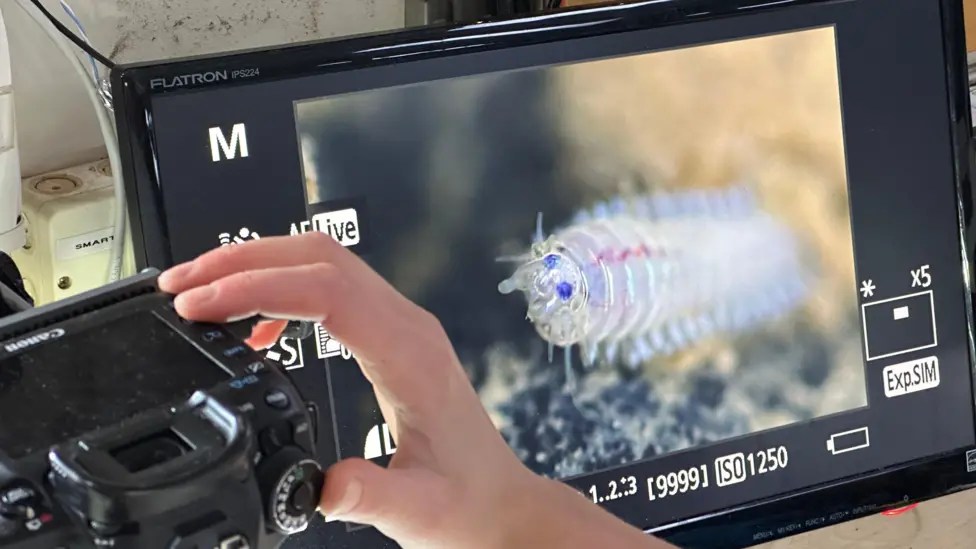

The scientists catalogued all the animals they found in the sediment, including this worm

How the study was done

The work was carried out by scientists from the Natural History Museum in London, the UK’s National Oceanography Centre and the University of Gothenburg, commissioned by deep-sea mining firm The Metals Company. The researchers stressed that they operated independently: the company could see the findings before publication but had no right to change them. They compared the seafloor two years before and two months after a test operation in which mining machines drove around 80km across the seabed. The focus was on “macrofauna” – animals between 0.3mm and 2cm in size, including worms, sea spiders, snails and clams. Inside the machine tracks, animal numbers fell by 37% and the variety of species by 32%.

Lead author Eva Stewart, a PhD student at the Natural History Museum and the University of Southampton, explained that the mining vehicles scrape away about the top 5cm of sediment:

Most of the animals live in this layer, so when it is removed, they are removed with it.

Her colleague Dr Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras from the National Oceanography Centre added that even creatures not immediately destroyed could later be killed by pollution stirred up by mining activity. Some animals may simply move away, she said, but it is unclear whether they would ever return or how long recovery would take.

In contrast, areas close to the tracks – where plumes of sediment settled – did not show a drop in overall animal numbers, though the mix of species changed. Dr Adrian Glover of the Natural History Museum said he had expected stronger impacts there but mainly saw shifts in dominance between species rather than a clear decline in abundance.

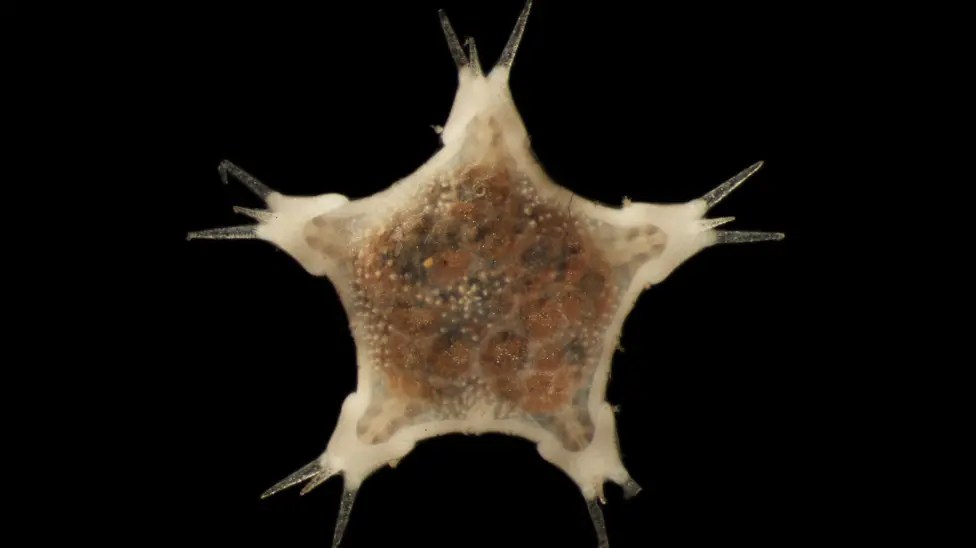

This sea urchin was one of the more than 4,000 creatures found

Industry and expert reactions

The Metals Company said it was “encouraged” by the results, arguing they show that damage is confined to the directly mined zones rather than spreading far beyond them, as some campaigners had warned.

But other experts interpret the findings differently. Dr Patrick Schröder, a senior research fellow at Chatham House, said the study suggests that current mining technology is too destructive to justify full-scale commercial operations. If even a limited test causes such visible harm, he argued, the effects of long-term industrial mining would likely be far greater.

An abyssal sea star was also found during the research

A high-stakes dilemma

The Clarion–Clipperton Zone covers around 6 million sq km and is thought to contain more than 21 billion tonnes of metal-rich nodules. With the International Energy Agency forecasting that demand for critical minerals could at least double by 2040, pressure to tap into deep-sea deposits is growing.

Yet many scientists and environmental groups warn that disturbing these largely unexplored ecosystems could have irreversible consequences. The deep ocean plays a vital role in regulating the planet’s climate and is already under stress from warming waters. Critics fear humanity might damage or destroy unique species and habitats before they are even discovered.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which oversees activities in international waters, has not approved commercial deep-sea mining, though it has granted 31 exploration licences. Thirty-seven countries, including the UK and France, support a temporary halt or pause on mining while more evidence is gathered.

Norway recently announced a delay to its own deep-sea mining plans, including in Arctic waters. Meanwhile, political signals are mixed: earlier this year, then–US President Donald Trump called for speeding up domestic and international projects to secure mineral supplies for military use.

If the ISA ultimately judges current methods to be too harmful, companies may be forced to develop less damaging techniques for collecting nodules from the seabed.

The new findings are published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, adding crucial data to a debate that will help determine whether deep-sea mining ever moves beyond the testing phase.